Dear Reader, in this age of AI created content, please support with your goodwill someone who works harder to provide the human-made. Sign up at the top of the lefthand column or bottom of this page. You will receive my hand illustrated monthly newsletter RESTORE NATURE and access to the biodiversity garden design course as I write...and nothing else, I respect your time. I am also removing the advertizing as best I can as its become intrusive inappropriate and pays me nothing.

The Cape hunting dog:

its symbolism and ecology

The Cape hunting dog: screen print of a three color drawing using spatter technique.

The Cape hunting dog: screen print of a three color drawing using spatter technique.The Cape hunting dog is a Shamanic animal in San mythology, perhaps because its one of the most effective predators on the planet. Yet it may be bound for extinction, due merely to it not being known or understood. Hopefully this article will help clarify why this is so. I hear a question: "What relevance do apex predators have to regenerative gardening ?". The answer is: everything.

This is the animal design of which I am the most proud, after a decade of making African animal designs. Making this design I did not have to pander to the pressure to produce the Hunter's Big Five to make sales. I never sold a copy of the Wild Dog design, it is there just because I love wild dogs. I also like it for aesthetic reasons. It would get my red stamp. I was going for something ephemeral, which captured life and expression, without getting into hard edged detail. To try for this I used ink spatter, which is very hard to control, necessitating some masking and a lot of tweaking post spatter. I chose ephemeral because this animal is so mysterious, so little known, magical, beloved of the oldest group of inhabitants of our part of the world, and because it moves like a ghost. It is one of the few predators which hunts by day, and therefore it has to imitate invisibility and silence to sneak up on its prey, after which it moves like the wind.

Apex predators and

regenerative agriculture

What would the Cape hunting dog have to do with regenerative agriculture ? Regenerative practice is based on replacing the beneficial influence apex predators once had on grassland ecosystems. They kept the herds moving, and thus gave the grass just the perfect amount of grazing, urine, feces and trampling, as well as the time to recover between each passing of the herds. Cape hunting dogs are by far the most skilled predators, and yet they are no threat to humans.

When, not if, we turn global agriculture around and use regenerative soil management to lock down the carbon that is killing us, and liberate the waters that will save us, the ghosts of the vanished apex predators like wolves and the Cape hunting dog will be our herd management mentors.

While they are still around, it may be possible to save the wild dog and use them to manage wild ecosystems regeneratively. Alan Savory

discovered that its not the herds of cattle which overgraze and degrade

the earth's soils, but the way they are managed. We might yet discover,

as we discovered there is a place for large ungulates or cows in a

future green world, that there is also a vital place for a predator like

the Cape hunting dog in a type of hands-off herd management, without

the need for so much electric fencing. They may be as important as the

cows economically, one day.

The Cape hunting dog's relationship with man

The Cape hunting dog, African wild dog, or painted wolf, Lycaon pictus, once broadly distributed through most African countries, is now critically endangered and extinct in many areas. The human-dog relationship has not been kind to the Cape hunting dog, and is marked by prejudice and an unjustified ugly reputation that licenses extermination, but it started differently, when canids were ranked among the gods.

The symbolic meaning of the wild dog is founded on hunting skill: creating order out of chaos and

association with death.

The Cape hunting dog was highly respected in hunter gatherer economies, for example in traditional San society and pre-dynastic Egypt.

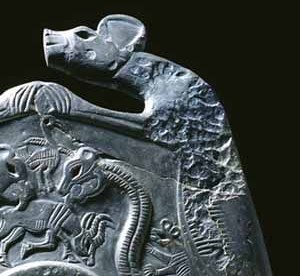

The wild dog was possibly first depicted in ancient Egyptian art of the pre-dynastic era in hunting scenes and border decorations. A clearly identifiable wild dog features in a heraldic 'shield' from around 3300 to 3100 BC. In pre-dynastic Egyptian art Cape hunting dogs also featured on cosmetic palettes. Perhaps because dogs and wolves represented the creation of order out of chaos, and the wild dog particularly was seen as a transition between the wild and tamed state.

The power they were believed to possess is reflected in a belief from Tigre that the Cape hunting dog could inflict instant magical death if attacked with bladed weapons, so they were scared off with stones and catapults.

Although the wild dog does not feature in historical San cave paintings of Southern Africa, they are associated with the origin of death in San mythology. Shamans could transform themselves into Cape hunting dogs and traditional hunters smeared their feet with wild dog bodily fluids in order to acquire the same agility and courage in the hunt, because Cape hunting dogs were seen as the ultimate hunters.

There is an Ndebele folk tale explaining why wild dogs hunt in packs, and so ferociously. They are the vengeful family of wild-dog's wife who died due to both Impala and Zebra's neglect in delivering her medicine timeously.

One of two African wild dogs encircling a five thousand year old Egyptian palette.

One of two African wild dogs encircling a five thousand year old Egyptian palette.The sacred status of canids in Ancient Egyptian art

During the early periods of Egyptian art, the greatest diversity of canids were depicted, but sometimes they are hybrid forms and their identification with species is uncertain.

The canine inspiration for the god Anubis, called the

jackal headed god, has been pinned to the golden wolf, a subspecies

of the grey wolf, or the more slender, pointy faced Ethiopian wolf

(which is now also highly endangered). However Anubis bears a greater resemblance to some other canids.

Anubis is one of the oldest Egyptian gods, and apparently developed from a previous jackal god. He was God of the dead, of mummification and the afterlife, ushering souls into the underworld, protector of lost souls and defender of the helpless.

Herodotus wrote that Egyptian wolves were as small as jackals, that out of respect they were buried wherever they died, and that wolves guided blindfolded priests to and from the temple of Isis. There is some evidence for wolf worship in various regions of ancient Egypt. Dogs or wolves accompanied the dead into the afterlife as guides. Dog sacrifice to Anubis was also so frequent that some dogs were bred specifically for sacrifice. The Egyptians did not distinguish between dogs and jackals linguistically.

This gives us some idea of the sacred status of canids in ancient Egypt. But Egyptians also loved their pet dogs. Owners expected to meet their pets in the afterlife. They were given names, elaborate collars, ritual burial and many more marks of esteem. The Egyptians developed many dog breeds comparable to modern breeds like whippets and greyhounds, Basenji, Ibizan, Saluki, the elegant Nigerian or Egyptian dog or Pharoah hound, which has an astounding resemblance to depictions of Anubis, I think. Lastly they loved small fast dogs like harriers.

The Cape hunting dog's social behaviour and breeding

The human fondness for dogs may arise from us both being highly social animals. Cape hunting dogs are no less social, showing many of the behaviour traits of highly social species. They have been known to share food and assist weak or ill members. Social interaction is common. They communicate by touch, actions and vocalizations

The wild dog's face is less expressive than that of the wolf. Perhaps because wolf hierarchy is more complex and wolves are separated for extended periods and must reintegrate without bloodshed, they need more capability to express subordination. Wild dogs stay together.

Gendered behaviour

The Cape hunting dog has some unique gendered behaviour. It is the only social carnivore where the females disperse, leaving the pack on maturity. This pattern is also found in some primates. There are both male and female dominance hierarchies. Females are usually led by the oldest female, males by the oldest or a younger one who supplants him, but the older ex leaders stay in the pack. The packs are usually led by a monogamous breeding pair. Usually only the alpha male and alpha female breed.

There is a higher ratio of males in packs, as females leave the pack, and probably do not survive. Females start reproducing by giving birth mainly to males. Then as females age they produce more and more female pups. This first drives up the number of male hunters and then when the group is stable, it ensures it doesn't grow too large, as the females disperse.

Breeding in the Cape hunting dog

Mate selection avoids inbreeding instinctually. Wild dogs will not mate with relatives. Because of declining numbers, unrelated mates have become less available and the avoidance of incestuous mating could lead to extinction. Available unrelated mates are crucial to their survival.

Copulation is of very short duration, to ensure the dogs do not become prey themselves. Gestation lasts about 70 days, and pregnancies are roughly a year apart. The female produces the most offspring of any canid, having litters of two to twenty pups. These are cared for by the entire pack. Subordinate adult dogs help feed and protect the pups.

As stated, breeding is limited to the dominant female. This is because the pack could not support more than one litter at a time, as the litters are so large. The alpha female may kill the pups of subordinates, and keeps her pups isolated for three to four weeks. Weaned at five weeks, they are then group fed with regurgitation. This is a way of providing food for the young and some other adults as part of social behaviour.

At ten weeks the young leave the den permanently and go on hunts. They are allowed to feed first on a carcass till they are a year old. Thus you may find puppies eating even before the dominant pair.

Hunting

Solitary living and hunting are extremely rare in Cape hunting dogs. The wild dogs sneeze to 'vote' on whether or not to go for a hunt. The decision is based on their being enough agreement, expressed as sneezes, and the hunt occurs especially if a dominant mating pair sneeze first.

The Cape hunting dogs and cheetahs are the only carnivores which hunt during the day time. Wild dogs can take down big animals like Zebra, with 289 kilos being the top prey size, but generally they prefer medium sized antelope, and the calves of larger animals. They will a tackle larger prey animal if it is ill or injured and supplement their diet with rodents and birds.

They hunt in packs of six to twenty or more. With falling wild dog numbers, larger packs are not found anymore. In the past even larger groups may have formed in response to the seasonal migration of springbok.

The wild dogs approach their prey silently, and then begin to chase as a group. Hunting strategies differ depending on the prey species. Large prey are repeatedly bitten in the legs, belly and rump till they stop running. Smaller prey are just pulled down and torn apart. The prey generally run in wide circles and the wild dog cuts off their escape routes. Medium sized prey are often killed in 2-5 minutes, larger animals in 30 minutes. Generally they hunt antelope by chasing them to exhaustion. Dangerous prey such as warthogs are grabbed by the nose by the males. Cane rats and porcupines are killed with a single quick bite well placed to avoid injury to the dog.

When chasing they can reach speeds of

66km/h or 41mph. The chase is kept up for ten to sixty minutes, and

the average distance covered is about 2km. This explains why they

need space.

The Cape hunting dog is a fast eater. A group can finish a Thompson's gazelle in a quarter of an hour. They eat one to six kilograms or about three to thirteen pounds of meat each per day, averaging at 1.7 kg or 3.7 lbs. Small prey are eaten whole. With large prey the head, skin and skeleton are left.

The wild dog's association with other predators

Lions dominate Cape hunting dogs and have destroyed entire packs. The lions will kill the wild dogs without even eating them. This shows they are are not hunted for food, but are highly threatening competitors for the same resources. On the other shoe, only old and wounded lions fall prey to wild dogs. Wild dog populations tend to increase only when lion populations fall, and more abundant lion leads to declining wild dog populations. When lions attack members of the pack, the wild dogs defend their fellows fiercely.

Spotted hyenas follow packs of wild dogs to steal their kills. The hyenas are only successful when attacking wild dogs in groups, but they do not collaborate as well as the wild dogs. The dogs retaliate as a group, driving off the hyenas by mobbing them. However, in the main, the hyenas disadvantage the survival of the wild dogs and their populations. As with lion, their population sizes correlate negatively with wild dog populations.

Cape hunting dogs tend to be very successful in the hunt. Often more than 60% of their chases lead to a kill, and success rates of 90% are not unknown. Comparatively, lion have a 27-30% success rate, and hyena 25-30%. However, a lot of the successful wild dog kills are poached by lion and hyena, who make up for their lack of hunting success by parasitizing the wild dog. Conversely, wild dogs are very rarely scavengers, and only occasionally steal carcasses from other predators.

This interaction pattern means they are out competed by other predators, adding to the pressure on their survival supplied by their breeding behaviour and human activity. Their prey is diminished by hunters and the space they need to run down game is taken away by human settlements. They have been treated like vermin by farmers and shot on sight for too long now, leading to their critical status.

What is not frequently mentioned, is that the tourist's and big game hunter's love for the big five and especially lions may favor keeping higher lion populations in some game reserves, for commercial reasons. This would drive down wild dog numbers.

A physical description of the Cape hunting dog.

Compared to other canids, the wild dog is the most highly adapted physically for two things, coat color and hunting. The hunting adaptions take the form of adaption to pure carnivory, seen in the teeth, and to bodily adaptions for extended running ability.

Its large round ears act like saucer antennae, picking up small sounds. Its long legs, greater height and lean frame give it more speed. The wild dog is 60-75cm or 24-30 inches at the shoulder. Only grey wolf varieties are taller. It weighs 18 to 36 kg or 40-79 lbs with females being generally up to 7% smaller. Its feet have one less toe, four rather than the five of other canids, meaning it has no dewclaws. The middle two toes are generally fused, increasing the power of its stride. They also have the metabolism to pursue prey for long distances.

The skull is shorter and broader than others in the dog family. Their carnassial premolars are powerful and built for shearing flesh, and are the largest of any predator relative to body size, bar its nemesis the spotted hyena. The carnassial molar has a cusp called the trenchant heel, while the lower teeth are adapted to cutting with reduction of the back molars. These two latter adaptions are found only in the Cape hunting dog and the Asian dhole and American bush dog.

The coat is mottled with patches of red, black, brown, white and yellow, giving each animal a unique pattern. The markings may be asymmetrical. The facial markings are much less varied. The muzzle is generally black, the cheeks and forehead brown, with a black line up the center of the forehead, and there may be a brown teardrop shape below the eyes. The back of the ears is generally blackish brown.

The coloring of wild dogs is one of the most varied among mammals. Why their coat coloring and form is so highly adapted remains a mystery. It may be for the purposes of identification and communication or concealment. When animals run long distance, it is often overheating which stops them. Unlike other canids, the wild dog has no undercoat, and its coat consists only of coarse bristles. It loses fur throughout life till the older adults are nearly naked.

The West African wild dog may be the only true subspecies.

The West African wild dog may be the only true subspecies.Picture attribution from Wikipedia: By Brendan Ihmig - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48969296

Variation in the wild dog

The coat colors show some geographic variation, but they do not delineate true subspecies.

The wild dog of the Cape has more yellow, with orange yellow fur overlapping the black, more yellow on the back of the ears, and underbelly, and white hairs on the throat. In Mozambique equal amounts of yellow and black are found on the upper body and underbelly, and less white fur. In East Africa the wild dog is much darker, with very little yellow, and the Somalian is smaller than the East African dog, with coarser fur, weaker teeth, and coloring more like the Cape dog, in buff, rather than yellow.

Recent genetic studies show they are not distinct subspecies and a lot of mixing has occurred in the past. Only the West African wild dog has a genetic haplotype unique to that group, making it a truly distinct subspecies.

Categorization of

the Cape hunting dog

Written records of the wild dog go back to suggestions in Oppian, a Graeco-Roman poet of the 2nd Century describing a hybrid animal, wolf like in form and leopard like in coloring. In the 3rd Century AD, Solinus described the 'Wonders of the World' and also a multicolored wolf, with a mane, in Ethiopia.

Temminck first did a taxonomic description in 1820, mistaking the dog for a hyena, and naming it Hyena picta, the painted hyena. In 1827 Brooks corrected this error, recognizing it as a canid, and naming it Lycaon tricolor, the three colored wolf-like animal.

The wild dog is the largest indigenous canine in Africa and the last survivor of the genus Lycaon. It is distinguished from the genus Canis, which includes dogs and wolves, by its teeth being made for hyper carnivory and its lack of dewclaws. It apparently diversified from the canids Cuon (Asian dhole) and Canis 1.7 million years ago, at about the time that ungulates diversified. The oldest fossil was found in Israel, and dated to 200,000 years ago, but due to lack of fossil evidence its evolution is little understood.

After genetic sequencing of the Asian dhole, there is evidence of ancient cross breeding between the two, and it is situated between dholes and side striped and black backed jackals on the genetic tree.

Naming the wild dog

The wild dog, having such a wide historic

distribution, must have many African names. These are only a few, and

they are only from southern Africa, which is not as linguistically

diverse as areas further north: Iganyana (Ndebele), Mhumi or Bhumhi

(Shona), Macebo (Mozambique), Mbwa mwitu (Swahili), Hlowa (Tsonga),

Lekanyana (Tswana), Dalerwa (Venda), Ixhwili (Xhosa) and Inkentshane

(Zulu). Looking for the root 'dog' in these names, I found only Mbwa

in Swahili meaning dog.

I found during studies of African lexica, that the names for indigenous animals are incredibly unique and varied, whereas the names coming from colonial languages are not so varied. Our numerous antelope are usually named something-buck in English and Afrikaans, whereas in indigenous languages the names are often short, and as different and species specific as cow and goat. Its not linguistic rocket science that the people who have spent the longest with the animals would have the richest animal lexicon. It is a tragedy that this rich natural terminology is being lost, and in the case of the indigenous language of Cape Town, Xirigowap, has been lost.

The wild dog's European names are somewhat varied, but following the colonizer's naming pattern. They turn around the idea of its colorfulness and similar appearance to a canid or hyena: wild dog, painted wolf, Cape hunting dog, African hunting dog, painted hunting dog, painted dog, hyena dog, ornate wolf and painted lycaon.

Apparently the term wild dog has such negative connotations for farmers in Africa that some conservation bodies call it by the name painted wolf, to avoid the prejudice that is helping to drive the animal to extinction, and permits it to be shot on sight in some countries.

The Cape hunting dog's habitats and endangerment

As can be imagined from its hunting style, the African wild dog frequents flat, open land, such as that found in savanna or arid zones, and is generally not seen so much in forest or mountains, although it will traverse such areas. There is a forest dwelling wild dog in the high altitude Harenna forest in Ethiopia. They have been sighted at high altitudes even on the summit of Kilimanjaro.

The wild dog was once found in all of sub Saharan Africa except in the driest deserts and lowland forest. There are records and suspected sightings in historical times from Algeria, Mauritania, Benin, Burkina Faso, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo, Cameroon, CAR, Chad, Congo, DRC, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Burundi, Eritrea, Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda (where it can be shot on sight), Angola and Eswatini. In these countries wild dogs have not been seen recently.

The wild dog is now rare in Ethiopia, Malawi, Kenya, Somalia and Sudan, and there are some almost sustainable breeding populations in Zambia, Mozambique, Tanzania, South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe.

It is estimated that about 6600 adults remain in sub populations threatened by habitat loss, disease and persecution. The largest, about 250 individuals, is yet too small for maintaining genetic diversity and thus the Cape hunting dog is listed as endangered. It is on the IUCN red list, who report they are probably in irreversible decline.

The wild dog has been known to hunt livestock, which is why they are often hunted by farmers. But they prefer wild food when it is available. Around human settlements they are vulnerable to the canine diseases like rabies and distemper.

The wild dog's survival

Wild dogs benefit from protected wildlife corridors between their fragmented habitats. This may help them find unrelated mates as they are very choosy about non incestuous breeding.

Conservation group initiatives work on reducing conflict between the wild dog

and humans, dispelling myths, creating awareness, and designing livestock

management strategies that prevent depredation. Rosemary Groom is one

of their many advocates. If you google wild dog conservation you can find a number of projects to support, large and small, as well as films to watch.

------

------

------

the greenidiom regenerative gardening blog

------

the all inclusive website blog

Restore Nature Newsletter

I've been writing for four years now and I would love to hear from you

Please let me know if you have any questions, comments or stories to share on gardening, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, food forests, natural gardening, do nothing gardening, observations about pests and diseases, foraging, dealing with and using weeds constructively, composting and going offgrid.

SEARCH

Order the Kindle E-book for the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023

Recent Articles

-

garden for life is a blog about saving the earth one garden at a time

Apr 18, 25 01:18 PM

The garden for life blog has short articles on gardening for biodiversity with native plants and regenerating soil for climate amelioration and nutritious food -

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, Cape Town's most endangered native vegetation!

Apr 18, 25 10:36 AM

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, a vegetation type found in the super diverse Cape Fynbos region is threatened by Cape Town's urban development and invasive alien plants -

Geography Research Task

Jan 31, 25 11:37 PM

To whom it may concern My name is Tanyaradzwa Madziwa and I am a matric student at Springfield Convent School. As part of our geography syllabus for this

"How to start a profitable worm business on a shoestring budget

Order a printed copy from "Amazon" at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

or a digital version from the "Kindle" store at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023