Dear Reader, in this age of AI created content, please support with your goodwill someone who works harder to provide the human-made. Sign up at the top of the lefthand column or bottom of this page. You will receive my hand illustrated monthly newsletter RESTORE NATURE and access to the biodiversity garden design course as I write...and nothing else, I respect your time. I am also removing the advertizing as best I can as its become intrusive inappropriate and pays me nothing.

Natural types of gardening

One of the ubiquitous natural types of gardening : A self sown wild flower meadow maintained by mowing.

One of the ubiquitous natural types of gardening : A self sown wild flower meadow maintained by mowing.This page introduces some types of gardening that have the aim to garden as closely to nature as possible. I invite you to share your knowledge here. Many millions of people are pursuing this goal in their gardens all around the world. The pooled knowledge of these gardeners, multiplied by their many decades of gardening, constitute a resource of immeasurable value. Unfortunately most of this knowledge remains in the minds of the gardeners and is not written up, published, recorded in any manner, nor widely shared. I am writing up my experience, and any other knowledge I can glean to provide a natural gardening resource. This is why I invite you to share here. You may help someone else enormously by doing so. I hope that my efforts and those of others doing similar knowledge collection will help counteract the loss of natural growing know how which is occurring as younger people migrate from the land to the cities, and the old folk with the deep knowledge slowly leave and all their memories are lost.

Knowledge loss in my family

I see this tendency for knowledge loss in our own family. My mother left the farm to get her education and become a 'professional' in the city, and she never absorbed my grandmother's extensive food growing and food preserving knowledge. I would love to know what my grandmother knew, even chat to her for a few minutes, but that is lost to me. My grandparents were mixed farmers and my grandma kept free range chickens, pigs, goats and cattle for their own use and sold eggs for money. She grew all the vegetables for the family table and her techniques were purely organic. She managed the mixed plantings in strips thickly mulched with straw and horse manure, and grew cane plants and other berries around the periphery to stop the drying winds in the desert. They had a mixed nut and fruit orchard for their own use, and larger commercial orchards for peaches and grapes. They made raw wine that they sold to distilleries and bred horses. They grew all their own rice and wheat, fodder and wood. They dried food such as peaches, raisins and made biltong (dried meat). My mother never tasted processed food from a tin till she was seventeen and I'm sure this is why she's still going strong at 92. My curiosity yearns for more, but that is the limit of what my mother remembers from her childhood on the farm.

What is 'natural' ?

There are theorists who say nature is just an idea of wildness in our own heads, and ‘nature’ is a construct. As such we are pursuing something, trying to imitate the function of the natural world around us, which we cannot see too clearly as its obscured by our own projections. On the other hand, some, like Ernst Gotsch, have called ‘nature’ an intelligent system, of which we are just a part. Personally, I cannot say that this thing, ‘nature’ is intelligent, but from repeated experiences, I’d propose that it is of a complexity that is unfathomable and the deeper we dig, the more hidden relationships we find that are part of its function as a whole. Thus it is dangerous to assert that one ‘works with nature’, it involves the assumption that one has understood it, and got a handle on how it works, and it's your partner, or heaven forbid, your servant. This kind of blindness has been part of our history as a species, and goes way way back to the dawn of our existence. Sapiens, the wise one, always wants to claim that he has understood, before he’s spent enough time on understanding.

That said, this page is about the pursuit of ‘nature’ and must include the failure to ‘catch’ it. Whether nature be an unreachable projection, that melts at one’s touch like a disintegrating mirror, or the uber intelligence in the cosmos, or a web of infinitely messy complexity.

A personal journey through some of the natural types of gardening

When you have this interest or desire to follow nature you will find yourself exploring many forms of thought similar to the ones I've encountered. I have moved through many nature aligned gardening movements that claim to ‘work with nature’, gathering useful thinking from each one. We are on a search for a type of gardening which undoes the damage humans wreak on the earth, and works wisely ‘with’ natural processes. Even if this is, ultimately, unattainable, or we don’t really understand what we are doing and why something ‘works’, we keep seeking. I feel that bowing to ‘nature’ is better in the long run for humanity than irresponsible disrespect, which can be evidenced in the state of our world.

My own pursuit of nature includes practical elements such as reintroducing native plants, supporting insect and wildlife diversity and creating all kinds of habitats for wildlife. It attempts to work against the localized effects of climate change, while providing phytonutrient rich organic food to the urban human. The goal of pursuing nature is multifaceted, yet encapsulated in one, extremely vague polysemic phrase: “gardening for life”.

I'd like to explore in writing the types of gardening which I've come across in the pursuit of nature, and write several articles on this. To start off I will outline my own journey on this page.

Conservation and botanical activism

as a type of gardening

Mom with the Table Mountain rangers in the indigenous remnants in Newlands forest.

Mom with the Table Mountain rangers in the indigenous remnants in Newlands forest.I include conservation as a type of gardening for two reasons. The first is that the transition between conservation and wildlife gardening can be blurred, it can be seen as an extreme on one side of the spectrum. The second is that if gardening is some kind of management or interference with the natural environment for the good of humans, conservation can be seen as doing just this and sometimes there is a high degree of interference. Examples are the pruning and felling of trees and removal of aliens, as well as the planting of native species that were once in a specific area, under the label of rehabilitation.

In my twenties I visited the wild veld north of Cape Town many times with my mother on her plant collecting trips as she listed all the species she could find on west coast farms in an attempt to drive their conservation. All of these 'wild' areas were on farms, and they were not strictly wild but mostly under some kind of grazing regime. This was necessary to keep the bush open so that geophytes like bulbs and annual flowers could grow, and the antelope that once did this were gone, so cattle were used.

We saw a lot of different management regimes and the results varied between high levels of degradation and incredibly rich and diverse bushy areas.

My mother was a dyed in the wool ‘conservationist’ in that she put enormous mental energy and all of her later life into protecting natural areas, but showed no inclination to wildlife gardening, or rehabilitating her own private space, and her own garden contained only aliens.

What I don’t like about some of conservation's way of thinking from the state side, is that if an area is not pristine, even slightly ‘degraded’ or contains some alien vegetation, it is written off and permits can be given for development. This was so a few decades ago. Considering the amount of degradation done by urban expansion, we can’t afford to do this anymore. Everything is degraded, and rehabilitation is needed even outside 'nature reserves'.

The wild part of my garden

The wild part of my gardenIndigenous gardening

Gardening only with indigenous plants was the type of gardening which started my own serious gardening journey.

Before that I gardened on balconies and in back alleys and knew only how to grow a few easy vegetables like beans, grow some succulents and take a few cuttings

In mid life I had the privilege to acquire a garden of roughly 20 by 15 meters, including the house, in the suburbs of Cape Town. The largest single open area of garden was a 10 by 10 meter piece at the back. First I dug out all the invasive kikuyu grass and the giant clump of exotic Bougainvilla in the center. Back-pained and ripped bloody, I covered the entire property 10cm deep in leaves by stealing green refuse bags from rich people’s houses in an area called 'the golden mile', and anchored the leaves with sticks and a few bricks. I researched on what native plants would do well in our 5 meter deep sand dune soil, spent (for my small means) enormous amounts at indigenous nurseries and planted up the garden with native perennials. For the first year I watered my young plants, and when they had taken I stopped watering. Further watering was unnecessary as all the plants were locally adapted. I had planted many trees including Vichellia karoo and two olives, sand olives and sand oaks, and some bushes such as bietou. What I didn't know at the time was that a forest can have 7 layers of a forest, nor did I have an ecological reason for choosing perennials. The choice of indigenous plants was limited to trees, shrubs, and a few common herbs and succulents found in local gardens. Nonetheless this garden thrived.

high up with chainsaw high up with chainsaw |

removing last vertical removing last vertical |

Indigenous tree choices

Two decades later the Vichellia karoo had grown into a groaning and growling monster impatiently scraping our roof with its claws, while we trembled below unable to sleep and waiting for tons of clay tiles to crash in on us !

These trees are not supposed to grow so large, but perhaps being raised on pure vermicast allowed it to escape its genetic chains. Cutting back the monster required an arborist who could abseil to bring it down. Anything but zero budget, which was my next gardening 'direction' ! But necessary work was needed to avoid damaging our home and incurring further expense. My first expensive gardening mistake and first lesson was to choose plants well in the city, which is full of buildings and they aren’t compatible with giant thorny trees.

However, to say something in its favor, and on natural gardening, the thorn tree was a bird condominium, a bespoke hotel for feathered travelers, and the diversity of avian visitors was impressive. After cutting it regrew very rapidly, and very densely. Hacking it back to a manageable height hasn’t really dented its appeal as accommodation. The minute the chainsaw noise was over, actually, a few doves were there indulging in their usual flirtations.

Formal training in gardening

After building my indigenous garden I was so hooked I began to study horticulture and landscape design by correspondence. After two years we had a practical workshop and I met the others for the first time. None of the students and lecturers believed I had a zero irrigation garden that was always green. I realized that if one makes one's money by installing irrigation systems which were a big part of the conversation at the workshop, one may be slow to realize that they represent excess and waste. I felt strongly that I would not be learning what I wanted to know in this context, and it wasn't my type of gardening. But in hindsight, I was rather impatient, judgmental and un businesslike. The next stage involved internship. I saw the terrible exploitation of laborers in the big horticultural industries in my country, and it was the final straw for me. I naively abandoned formal gardening education after about three years of study. The best part of it all was that I had got to work with a wonderful landscape designer famed for her beautiful borders, who became a friend, or at least showed readiness to mentor me. She was over 80 and still working, an illustration of how gardening insight improves with experience.

Zero budget gardening

After a spell at university, acquiring a largely useless Master's degree in linguistics, I moved back to the garden and my husband. Being unable to find work as a linguist I started creating this gardening website. My husband gave me free reign to replant the garden, because all the native plants had been removed when he needed space for his vermiculture business. All except the giant thorn tree and the olives.

This time I gardened on a zero budget, and ironically, zero budget gardening became a core gardening strength in time and the type of gardening I love the most. I learned to grow everything myself, and in the end the time taken was worth it. I don’t go to nurseries to buy plants any more, and the limits on what I can do in the garden do not depend on having money for plants. Zero budget limits what I grow only a little. I’ve even grafted male branches onto a female fruit tree of a different variety successfully, so that pollination could occur.

In the very beginning I used various easy growing weedy plants from my mother’s garden just to get everything covered as quickly as possible. I didn’t bother about whether they were natives, they just had to be tough and free, and slowly I’ve enriched the plantings over time.

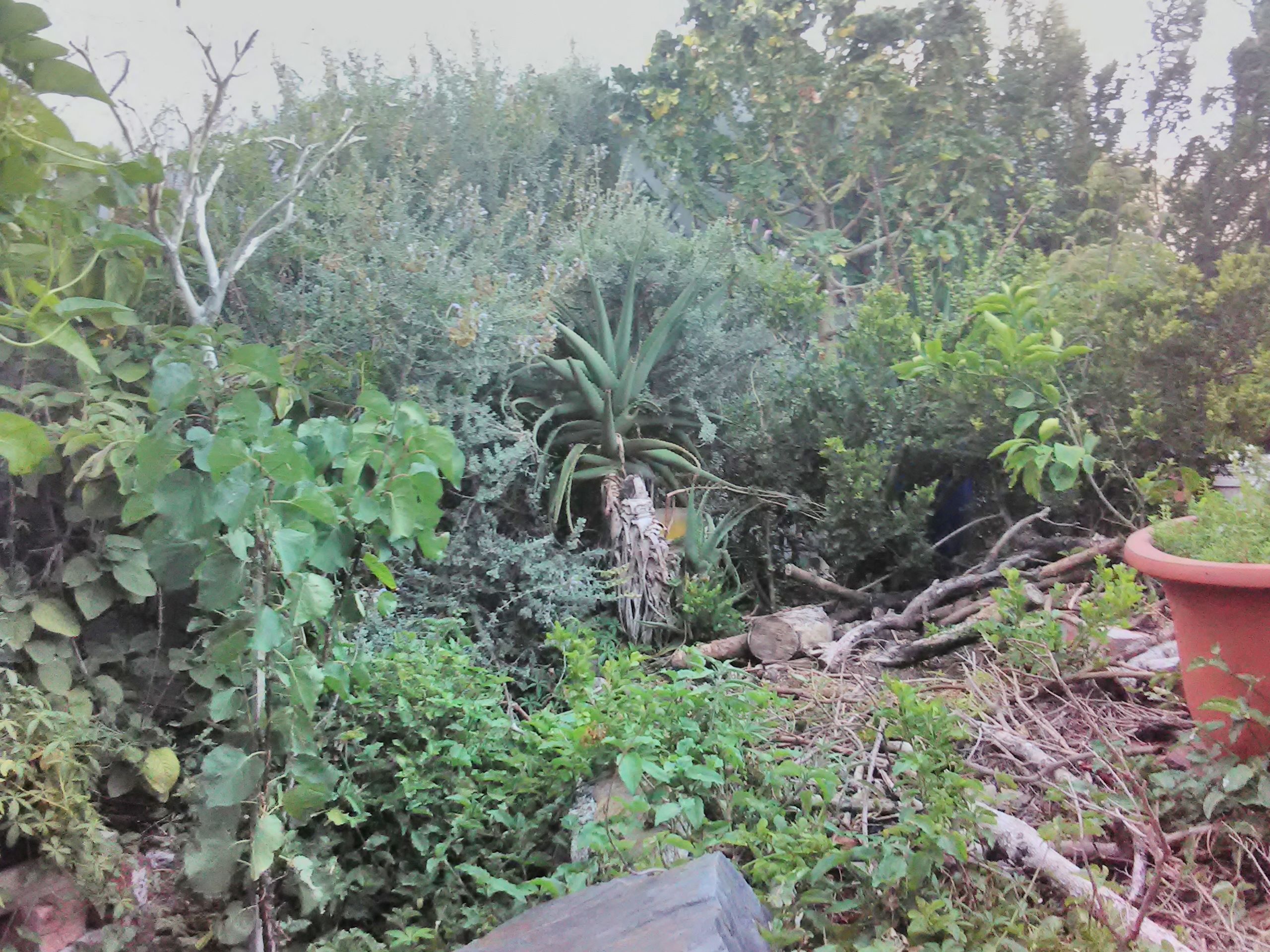

I feel mixed emotions seeing this picture. A lovely sisal plant topping 3 meters, but what poor ravaged and naked earth. This type of 'gardening' is the norm in my hood.

I feel mixed emotions seeing this picture. A lovely sisal plant topping 3 meters, but what poor ravaged and naked earth. This type of 'gardening' is the norm in my hood.Full cover, no naked soil

My lesson in replanting on a zero budget was that plants like plants. Generally speaking. I believe in just filling the space, and not having empty areas between the plants. This way magic can happen. I only understood more of of how this works later when I learned about soil life. I did not realize how this observation was going to integrate into my later exploration of other types of gardening.

The subtext to 'plants love plants' was the next next lesson. It underlined the issue of having no naked soil. Walking the dog around my area I saw many gardens in which naked earth caused stunted growth, yellowing of leaves and plant death. Only the very largest plants had some vigor. I didn’t know why at the time, but I wrote about it, wondering why people literally weeded their gardens to death.

Using resources you have wisely

To relieve the compost toilet I built a urinal with a lead into a fermentation tank.

To relieve the compost toilet I built a urinal with a lead into a fermentation tank.I'd always been concerned about using less water in the garden as it seemed so wasteful to irrigate. I began to think about resources and minimizing inputs, especially working with water conservation in the garden. One of the types of gardening that emerged in my search was the water wise garden. This type of gardening is often needed in dry areas like deserts, or in areas which are dry for part of the year, especially if this is the summer, putting heat and desiccation stress on plants at the same time. I read about Heidi Gildemeister’s ‘water wise’ gardening methods in the Mediterranean. We have a similar but much drier climate, and I learned so much from her about managing water resources, and how plants have adapted to drought. I took a lot of photographs at Kirstenbosch which is our local botanical garden, for these articles. Much later I discovered Brad Lancaster’s more radical desert gardening and water harvesting ideas. I’m trying to fit them into a garden that is already planted, and its not easy. Building tree pans is about all I can do, but there will be some excavation coming up, possibilities to dam and collect runoff. The lesson I’ve learned is

"if possible, do your water collection and distribution plan first, as the foundation of your garden, which will determine what you plant where".

Retrofitting your water collection is piecemeal, untidy, difficult and may require digging up established plants, or letting some die. Unfortunately I didn’t have much choice, because of my zero budget gardening and tanks being expensive, and the sequence in which I acquired the knowledge. What I did discover after planting the garden was what a valuable and plentiful resource the kitchen greywater was. I’ve found low tech ways of distributing the water to where it’s needed, as well as blending it with fermented urine. Both liquids are conveyed in small flexible pipes that lie on the surface but feed into the ground, as per city regulations.

Under the cover of permaculture: setting up for a workshop in Langa township.

Under the cover of permaculture: setting up for a workshop in Langa township.Permaculture: one of the types of gardening naturally

After going ‘indigenous’ and ‘water-wise’ I discovered permaculture, and found it to have enormous explanatory power as a type of gardening that is concerned with ecological methods. It integrated much of what I was beginning to learn and was the closest to the type of gardening I wanted to do at the time. I completed a permaculture design certificate, and worked for two years as a volunteer, writing about permaculture workshops I attended in my city. My only disappointment was the lack of interest in native food plants I encountered, and the tendency to conform to a set of plants grown world wide in permaculture gardens, you know the sort of thing: comfrey, tamarillos and so forth. This was perhaps a fault of permaculture itself. It does advocate ‘local solutions’ but perhaps the fault is that it doesn’t clarify that this should include using more native plants, nor does it elaborate on why native plants are so beneficial. Left to their own interpretations, permaculturists often just go with what is common in the global perma-culture. In time I realized I needed something with a much stronger indigenous plant emphasis. Nonetheless I frequently consult my course notes when designing new systems or thinking about tweaking my practice. Permaculture has a lot to offer that you can't get elsewhere.

Composting is gardening with microbes

My two pentagon composter. It leads to much more thorough composting than a cube built with pallets as it allows a thicker wall of organics.

My two pentagon composter. It leads to much more thorough composting than a cube built with pallets as it allows a thicker wall of organics.Around this time our city was struck with a terrible drought and I began to use compost toilets. This compost has been indispensable for growing food, as I don’t keep poultry or small animals except worms for the purpose of harvesting their manure. A friend of mine had a wonderful idea to started a composting business, and it evolved through many elaborations. Given my husband’s experience running a vermiculture business it would likely have been a success. I’m sorry I abandoned that possibility because of being too obsessively interested in plants and too little in composting.

Forest building as one of the natural types of gardening.

My mom with her other children, the native yellowwoods she planted in Newland's forest to fill the gaps left by exotics such as oaks when they fall.

My mom with her other children, the native yellowwoods she planted in Newland's forest to fill the gaps left by exotics such as oaks when they fall.I first learned about food forests from permaculture, and there learned about the forest layers and succession. This fed back into what my mother learned about forests on Table Mountain at Newlands, and thus my interest in forests increased. It is also a type of gardening in a sense, as it involves human input and sometimes organizing enormous projects, to work with nature for the benefit of humans. I completed a webinar on forest building under Shubhendu Sharma and his company Afforest, and tried to start a forest building business at the UN SEED startup workshops. I happen to know from how we best plant our local forest trees that Afforest’s technology would have needed to be adapted to the conditions favored by local species. Raising native trees from seed was challenging too. At that stage I became distracted from my purpose be finding employment in a nursery.

My native fruit tree nursery.

My native fruit tree nursery.I had a backyard nursery with all the things I grew myself and planned on selling them to the nursery that employed me, and to township gardening NGO’s. I grew native fruit trees. It didn’t resonate and years of care were just wasted when absolutely no one wanted my trees, not even when they were going free. Keeping a tree nursery may seem low labor at first until you reckon in the weeding, repotting and watering. I took in R400 eventually, selling just one species, but it was a loss against all the costs. A lesson about the nursery business: I realized the knowledge of what plants ‘sell’ is vital to survival as a nurserywoman, and understood more of my employer’s struggles with intellectual theft of this kind. My garden eventually was to benefit from this failed business as I overplanted my perimeter, stuffing in the fruit trees to be removed selectively later, and I’ve still got a stock of trees which are getting stunted in their tiny pots. Keeping them small is good. I hope to plant them at the start of the coming rainy season.

Lessons from regenerative agriculture

My thirty species cover crop mix cost next to nothing.

My thirty species cover crop mix cost next to nothing.Another big learning experience came with learning more about soil. I managed to get into a free soil advocacy course with Kiss the Ground which explained the infertility of naked earth and a lot of other things, that had bothered me before, and it was very enriching. The basic theory of building rich soil with 5 principles. One of the principles is to plant diversity, and this means at least 15 species in one area. It is at this level of diversity that the increasing benefits of diversity with each added species begin to plateau. I explain further in my regenerative blog on this page.

Regenerative agriculture is another school of thought or type of gardening. All the knock on benefits brought by the ‘soil sponge’ give a brilliant, simple insight. But its not perfect either. I skip forward to later learning, in order to qualify this.

The point of regeneration is to create very fertile soil by supporting soil life. However, in a highly biodiverse garden one cannot eliminate low nutrient soil habitat. It is necessary for diversity.

For proper flowering plant diversity, low nutrient soils are a must in many areas of the world such as Germany, Britain, even the North American prairies, but especially for our fynbos where the soils are so low in nutrients that high nutrients can kill many fynbos plants. You can’t just add animals everywhere. The fynbos was never perennial grazing country. It doesn’t mean our soils did not lock down carbon or have some soil organic matter. Our low nutrient soils were probably full of natural ‘biochar’ because we have a fire dependent ecology. The ancient bushes have deep underground root systems that smolder after a fire for months sometimes.

If you turn everything into a rich bacterial sponge as advocated by regenerative agriculture, flowering plants will be greatly reduced in diversity in many areas of the world. Insect diversity depends on the diversity of flowering plants. So ideally we cannot just regenerate soil with plenty of animal input and controlled grazing, everywhere on the planet, not if biodiversity is a goal. We need to keep pockets of poor soil for the flowers. Those who have ears let them hear. The ideal would be a mix of soil habitats, of low and high nutrient soils. The regenerative techniques I learned, such as diverse cover crop seed mixes, do work for enriching soil, and turned areas of my garden plagued by aridity into dense stands of mixed edible greens. You can see my regenerative garden blog for photographs and descriptions.

Some different types of gardening with wildlife

Arum motif with Hummingbird hawk-moth larva.

Arum motif with Hummingbird hawk-moth larva.Long before this I had started doing botanical designs for screen printing by hand, with rotring ink on film way back in 1994. Years later, at about the time I discovered regenerative agriculture I started digitizing my botanical designs for Redbubble. During my write up for each flower on this website I discovered incredible insect to plant relationships, before I was really aware of their interdependencies as a thing to bear in mind when gardening.

Providing habitat with an insect and reptile hotel inspired by Markus Gastl

Providing habitat with an insect and reptile hotel inspired by Markus GastlThen I stumbled on videos by Markus Gastl. Fortunately I understand some German. He expressly and laboriously built very low nutrient soil to support flowering native plants and thus insect diversity in Germany. You will be astonished, if you read more about him, just how much his soil management is the polar opposite of regenerative agriculture, except in his focused food growing areas. In the photograph above the naked earth around the insect hotel was soon covered by my multi species cover crops to make an ideal insect garden.

A steppingstone corridor garden being pegged out in the arboretum. You can just see the forest of thousands of young agave in the background. In South Africa they are invasive aliens but they were also Mexico's staple carbohydrate crop before maize gained ascendancy there. Can't we harvest and eat them instead of spraying with herbicide ?

A steppingstone corridor garden being pegged out in the arboretum. You can just see the forest of thousands of young agave in the background. In South Africa they are invasive aliens but they were also Mexico's staple carbohydrate crop before maize gained ascendancy there. Can't we harvest and eat them instead of spraying with herbicide ? Our ecological guide giving us a tour of Communitree's stepping stone gardens.

Our ecological guide giving us a tour of Communitree's stepping stone gardens.Finally I discovered the NGO Communitree which focused on building stepping stone wildlife corridors by rehabilitating degraded verges and corners of the city. They were friendly and extremely accessible, despite having busy lives. I linked up with another stepping stone garden network in the northern suburbs of Cape Town, because at that time Communitree was only in the south. I learned a lot from these groups about rehabilitation strategies, and how to find plants that are truly local, rather than just having some vague indigenous label. Hybrids between local plants and showy nursery varieties can form ‘Frankenstein plants’ which take over and push out the local wild varieties. If local insects are not evolved to access the nectar in the hybrids, they can die out. That is the danger with ‘native’ plants that are not native enough. Our limit is a 10km radius.

Foreign showy flowers from other countries do nothing for most indigenous insects. Planting exotic flowers for honeybees is nice but it isn’t doing anything about the global loss of insect diversity. Equally, I learned that most of my ‘native’ fruit trees were probably not doing much for insect diversity either, as they came from a locality, originally, that was a thousand kilometers away. The lessons never stop. We look back on ignorance again and again.

Later my long held dream (laid out in an article in about 2016) of crossing the city with a network of green arteries of native vegetation along the rivers which people could enjoy and wildlife could use became realized in Communitree’s future strategy plans without me doing anything. Its a beautiful idea and I hope it just keeps on growing and becomes real on the ground.

Community gardens and pest control

Along came COVID and our local CANs or collaborative networks and there was a massive urban gardening movement that started up. It was beautiful to witness. Pests can reduce yields in a food garden considerably. I wrote about how to do all this food growing in a more soil and wildlife friendly way without using poisons like Neem. Research on brix values and insect herbivory show that aphids are the lowest on a pyramid of pests, and are a sign your garden is sick, underground. Better to deal with them as a call to action by going for the cause rather than the symptom.

Is foraging invasive aliens another one of the natural types of gardening ?

Around this time I prepared a guided tour of our arboretum, as I have foraged there so often. The tour was showing how all the invasive Meso American aliens could be controlled with foraging, as they were all edibles, delicious ones at that, which we don’t know how to eat here. They need to be removed from the wild, or strictly controlled because they are invasive. Meanwhile some of them are delicious and nutritious wild vegetables. But for us food is from Europe, must require many inputs and much effort, and crown the successful grower rather than the successful plant. My message didn’t resonate at home, so I continue to write in hope.

A traditional Mexican green vegetable plant we know well in South Africa, but here it is an invasive plants and we only know and use the fruit.

A traditional Mexican green vegetable plant we know well in South Africa, but here it is an invasive plants and we only know and use the fruit.Traditional types of gardening from

Meso America

During my reading, without it being particular to any course of study, I came across the brilliant gardening methods of meso-America, from terra-preta to the floating gardens or chinampas of Mexico city, and the Mayan pet kot or walled forest gardens. I hope the Athlone sewerage dams will be turned into chinampas soon. Just putting it out there, you never know who’ll read this.

Central America gave us nearly half of our vegetable species.

Traditional techniques and types of

gardening from China

Another rich source of plants was China. I binged on Li Ziqi’s beautiful videos and read King’s book on farmers of forty centuries which outlines soil conservation methods in the flat plains of China and east Asia. I realized ‘permaculture’ had a major debt to the Chinese, and to the title of Kings original manuscript.

Stacking in space and time, mixed inter planting, harvesting young and recycling everything back into the garden are some examples of earlier Chinese growing genius. I binge on Chinese videos frequently, but there is no one like Li Ziqi, and I hope she hasn’t permanently stopped making films.

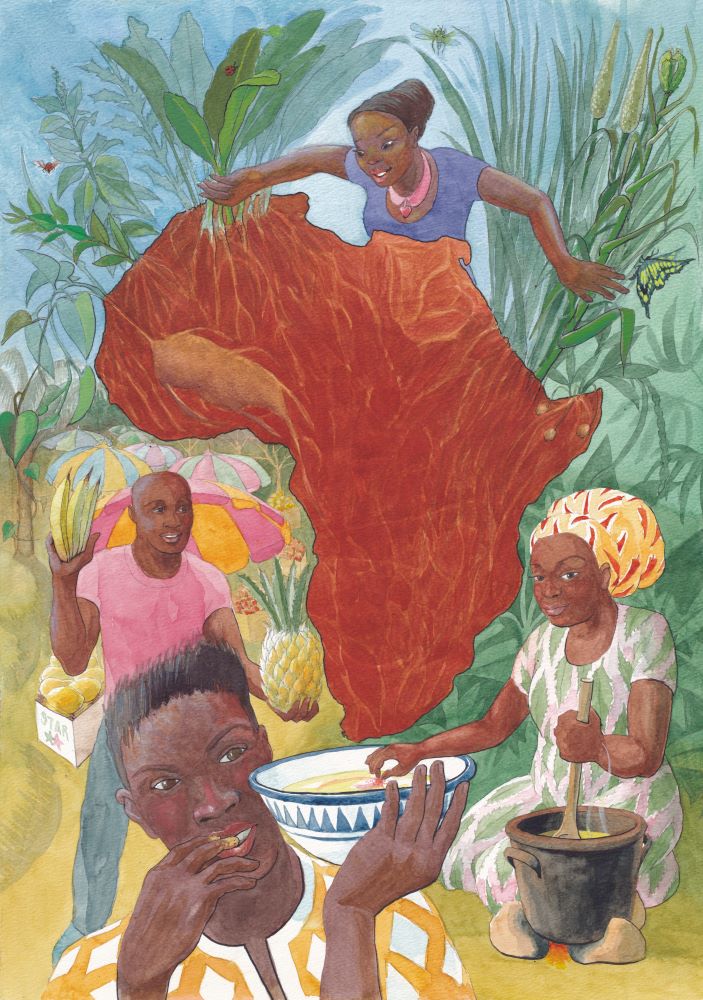

The cover I created for a book on traditional African gardening, vegetables and cooking

The cover I created for a book on traditional African gardening, vegetables and cookingTraditional food plants from Africa

Recently I illustrated three books on African agroecology and learned so much about African vegetables, and growing these sometimes ancient food plants has turned into an adventure. Even the tropical plants grow better here in our entirely different climate, than European vegetables.

Is doing nothing one of the types of gardening ?

I read the one straw revolution by Fukuoka and realized I’m a ‘do nothing’ gardener like my mother. For a do nothing gardener my back is often sore and my skin torn by thorns, and I’m covered with brown dust at the end of the day. Another lesson learned is that hands off management is really hands on. Once you’ve set up your systems, there should be less work required, they say. Theoretically this should be the case. However, there are two reasons it doesn’t happen. When the system is pumping out biomass which you can scarcely keep out of the neighbour’s gutters and is poking the eyes of pedestrians on the pavement, cubic meters of ‘garden waste’ a month must be harvested, and yet the forest keeps expanding. Your problem becomes how to deal with biomass, and I only have a 100 square meters of garden ! The second reason is that your idea of the ideal system that allows you to eventually do nothing may keep changing, requiring digging, building and uprooting in a constant turnover of ideas.

I just keep throwing new plants at this setup. I grow plants from seed gathered around the city or bought online, culture odds and ends bought at the Chinese grocer and other food stores and put back in my garden. When I raise plants for the perimeter hedge I do some research and pick plants that play host to many native insects such the bietou Chrysanthemoides monolifera, and sour fig Carpobrotus edulis. However, my experience with Communitree has taught me that to support insect diversity very precise locality is necessary in this so very diverse Cape Floral Kingdom. I am starting to raise plants whose seed has been gathered within a ten kilometer radius, to put back in my garden and in local parks.

Three zone permaculture in my garden

The garden and my thinking have eventually crystalized into a very scaled down urban integration of many types of gardening, something like Markus Gastl’s three zone permaculture.

Zone 3. The perimeter forest

There is a wild perimeter hedge of fruit bearing thorny trees, with many piles of dead wood and some lizard hotels built out of piles of broken concrete. I have planted thorny wild asparagus, Opuntia, tick berry, wild plums (Carissa and Harpephyllum), Kei apples and bamboo in the perimeter zone too. At present this is where I harvest berries.

Blooming wildflowers are a useful wildlife supporting part of any natural garden.

Blooming wildflowers are a useful wildlife supporting part of any natural garden.Zone 2. A low nutrient flowering zone.

In the middle of the garden is a large area of scrubby low drought hardy vegetation with a lot of native flowers and Mediterranean herbs, always crawling with bees, and some classic fruit trees like mulberry, lemon, tamarillo, carob and apricot. At present it gives me herbs for the pot and medicinals.

Zone 1. High nutrient food growing zone

In the long passage which used to be a driveway on the sunny side of the house is the high input area. There you will find the nursery and the greywater and urine lines, organic mulch, compost, fermented kelp, manures and so on going into containers and raised beds. This is where I grow my exotic non-adapted vegetables such as dill, tomatoes, maize, okra, cabbages, sweet potatoes, beans and turnips. I found that the main nutrient, something northern gardeners take fore granted perhaps, is water. Add water and most of your oleiricultural problems at the Cape are solved. Previously I couldn’t really afford to harvest water, because I can’t afford tanks. But grey water is an incredible source of this fabulous nutrient. However, it blows me away just how much support these plants need in our climate and soils. Growing these foods at the Cape is water intensive and we really shouldn’t be growing them as staples, especially not in our treated drinking water.

In the high input area are some beds which actually have very high water content, my grey water grow beds are basically bogs, in which you’ll find waist high chard and Malabar spinach, Italian dandelion and beets. Our fish pond filters are entirely water, like aquaponics, and water spinach and cherry tomatoes thrive there. A very sunny bed on the street, which is fed by aged pigeon manure, has giant African amaranth in it, and is watered much less often.

Is this the end of my exploration of

natural types of gardening ?

After a long journey I’ve reached a sort of plateau, a methodology which satisfies much of me, and I’ve lost the need to be searching for another ideology, and rather want to focus down on improving my horticultural skills with growing natives within this conceptual framework. I hope I’ll find some day that it isn’t the ultimate goal, and continue the quest. At present this resting place is something like three zone permaculture in its structure, as previously mentioned, with its outer perimeter, its thin soil, and its fat soil zones. In intent it is more like wildlife gardening or wildlife corridor creation, and on the level of plant material its as native and perennial as possible, given the history of the domestication of food plants. We will all do this mixing differently, in our own corner of the world, but for me thus far its the best way I’ve found of uniting the gardening that needs to be filled for the my health and the health of the planet.

After 10 years of not knowing where I’ll be living at years end, living a necessary nomadic existence between my husband and mother, I’ve finally insisted that my forest garden is not going to be sold off, and I’m staying, most of the time, where I am. It is necessary that I go on gardening, find the time and the space, as its my major source of respite. .

Syntropic gardening

A few days ago I took a second or third look at Ernst Gotsch, and this time it held a lot more appeal and made so much more sense. I can see a new set of principles that I need to leverage in the service of natural gardening. Using succession and maximum photosynthesis, and pruning to encourage growth all have multiple benefits that I’ve learned of through other gardening philosophies, science papers and garden experiments. I hope to find out exactly how his methods lead to maximizing biodiversity when exotic food plants are used, and what form of climax forest he is building.

--------

home page for links to soil, water, plants and other aspects of natural gardening

Restore Nature Newsletter

I've been writing for four years now and I would love to hear from you

Please let me know if you have any questions, comments or stories to share on gardening, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, food forests, natural gardening, do nothing gardening, observations about pests and diseases, foraging, dealing with and using weeds constructively, composting and going offgrid.

Your second block of text...

SEARCH

Order the Kindle E-book for the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023

Recent Articles

-

garden for life is a blog about saving the earth one garden at a time

Apr 18, 25 01:18 PM

The garden for life blog has short articles on gardening for biodiversity with native plants and regenerating soil for climate amelioration and nutritious food -

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, Cape Town's most endangered native vegetation!

Apr 18, 25 10:36 AM

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, a vegetation type found in the super diverse Cape Fynbos region is threatened by Cape Town's urban development and invasive alien plants -

Geography Research Task

Jan 31, 25 11:37 PM

To whom it may concern My name is Tanyaradzwa Madziwa and I am a matric student at Springfield Convent School. As part of our geography syllabus for this

"How to start a profitable worm business on a shoestring budget

Order a printed copy from "Amazon" at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

or a digital version from the "Kindle" store at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023