Dear Reader, in this age of AI created content, please support with your goodwill someone who works harder to provide the human-made. Sign up in the righthand column or bottom of this page. You will receive my hand illustrated monthly newsletter RESTORE NATURE and access to the biodiversity garden design course as I write...and nothing else, I respect your time.

Should we care about loss of biodiversity ?

Questions about and questioning loss of biodiversity

Questions about and questioning loss of biodiversityGARDENING AGAINST EXTINCTION

PART 1

Hello subscribers !

This is part 1 of the biodiversity gardening course I'm designing. I thought that before launching into gardening remedies for loss of biodiverstiy, and how to design your own garden from the ground up, I should take a closer look at this idea of biodiversity and interrogate it a bit. I found out it is quite a new concept, only 38 years old in fact !

I hope you enjoy this section of the course. Feedback is welcome, in fact I'm hungry for it... so please DO feed the animal !

Is biodiversity really in decline ?

Is there really so much loss of biodiversity ? Are we really in a crisis, the midst of a mass extinction ? Isn't that just a wee bit sensationalist ? If you have ever wondered, I have too, and the following article outlines my quest for answers. But this does not pretend to be a scientific paper. I favor writing on gardening for gardeners who need practical 'how to' solutions.

The big issue: biodiversity

The prominence of the concept biodiversity dates back to a conference held by Jared Diamond and E.O. Wilson at the Smithsonian in 1986. Their platforming of the idea was criticized as a politcal manoever, that biodiversity 'marketing' was as viral as the marketing of Madonna and only white men sat at the conference. This doesn't mean the idea of biodiversity is wrong in itself. Indeed the subsequent arguments are mostly around social contextualizing, understanding, applying and naming 'it'. Ideas don't have to be marketing failures to be really important.

So, loss of biodiversity is now a global concern claimed to be more dangerous than global warming. Most agree that biodiversity and climate change are intimately interlinked (Lindwall 2022), (Shaw, 2018), (University of Wageninen 2022). As with the climate debate, approaches are diverse, including some which are intentionally confrontational and controversial, those which are alarmist and those which are denialist.

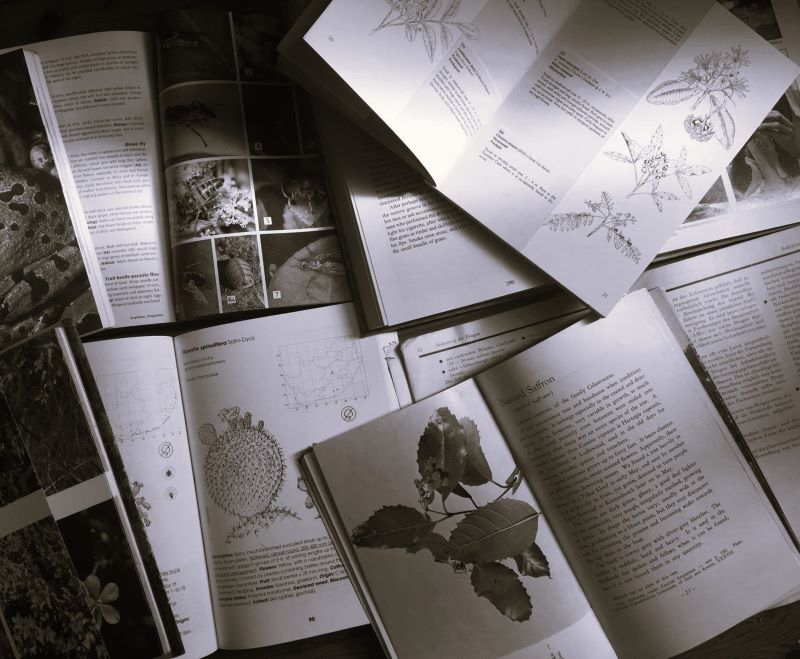

My dictionary, from back when I was a biology nerd with pigtails. Not much has changed since then, except the dictionary.

My dictionary, from back when I was a biology nerd with pigtails. Not much has changed since then, except the dictionary.What is biodiversity.... really ?

Biodiversity means many things to many people (Vellend, 2017). It has been defined as “the variety of life in our natural world” (Lindwall, 2022) “the variety of all living things and their interactions” (Smithsonian) “the different kinds of life you'll find in one area” (Hancock). That is pretty much the gist of it. As you can see its a woolly idea.

The very vagueness of the concept is the cause of some of the contention in discussion on biodiversity (Fieseler, 2021). One could focus on many kinds of difference or variety in life forms, many different kinds of biodiversity. There is genetic variation, which can include phylogenetic relatedness or genetic diversity within a species. It can mean the numbers of species in a locality, or the functional diversity, which can likewise mean many things, from the diversity of functional roles, to the diversity of organisms filling each role. It can refer to the diversity of native organisms in an area, or the diversity of all organisms, irrespective of origin, or to the variety of ecosystems. The area where the biodiversity is located can be a specific habitat of a few square meters, an ecosystem, biome, locality, region, country, continent, climate zone or the whole globe. We could even study the biodiversity of the Milky Way galaxy with advanced space travel !

What about the scientists who say there is no loss of biodiversity to worry about ?

The literature brought up by google on the biodiversity counter narrative focusses on the work of Pyron and Vellend.

Pyron seized worldwide attention in an article in the Washington Post stating that extinction is part of evolution and we should stop trying to save endangered animals (Pyron, 2017).

It pays to read the original because some of his critics suggest he doesn't believe there is loss of biodiversity. Pyron clearly states we are in the middle of the 6th mass extinction event. It is about our attitude to it that he makes his inflammatory criticism. We should not worry, and just adapt to living in a world with fewer species.

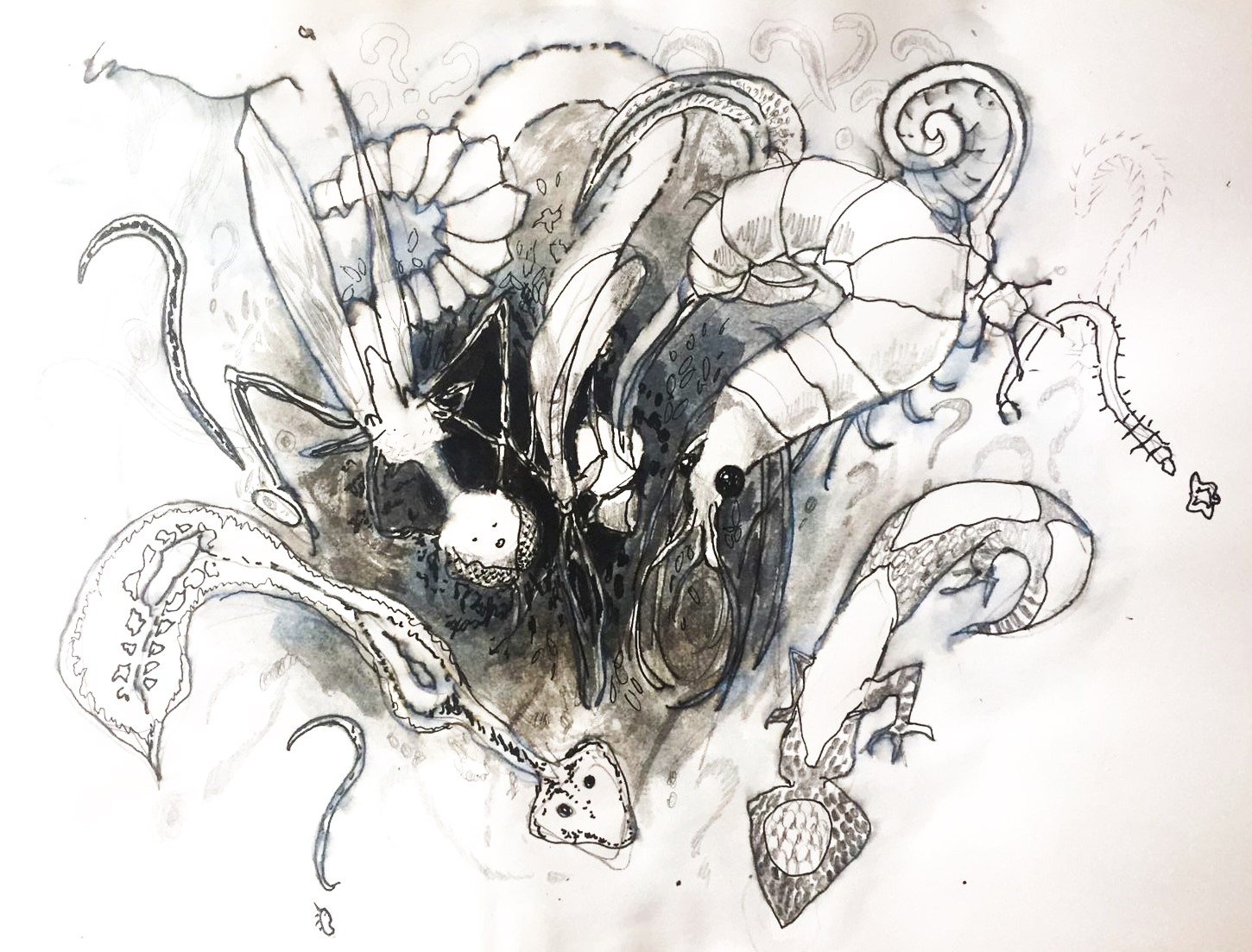

The intertidal zone is embattled. It is a narrow band of rich resources where turf is fought over with tooth, claw and poison. We find the bleached remains of the losers pretty. Its all about perspective isn't it ? or is it not ?

The intertidal zone is embattled. It is a narrow band of rich resources where turf is fought over with tooth, claw and poison. We find the bleached remains of the losers pretty. Its all about perspective isn't it ? or is it not ?Amid the ensuing furore after his proclamation, when he was attacked by an army of angry ecologists, Pyron admitted he was trying to be contentious and dramatic and open up the debate on biodiversity. That may be. He also attracted a lot of attention. It was mostly negative, and as with the algorithms, negative attention decides how interesting you are.

What he has to say is about extinction is actually unremarkable. It is his interpretation of how we should react that is so offensive to people. For example Pyron declares that there there is no moral imperative to save species even when we have caused their extinction.

He rails against what he calls pointless conservation, attacking those trying to save single species like snow leopards, chimps, rhinoceroses and pandas. These cases are used to condemn biodiversity conservation in general. This ignores attempts to conserve the biodiversity of whole ecosystems, which is the goal of biodiversity conservation.

What he also ignores is the marketing value of these star species for conservation. Concern for chimps can serve as an introduction to whole system thinking, and concern about the biodiversity of the chimp's habitat, and social concern such as reducing poverty and human conflict which are the ultimate cause of much endangerment.

He also must have created scientific backing for denialists. I privately wonder how many species have already been endangered or lost because of scientists providing denialists with so called proof that we don't have a problem.

Scientists in the cherry orchard

Vellend (2017) argues justifiably that man does not always impact local biodiversity negatively, even if global biodiversity is reduced by our species. He admits that clearing for agriculture and buildings does reduce biodiversity, but that introduced species sometimes do and sometimes don't decrease biodiversity.

He adds that advocates for biodiverstiy should be honest that their love for global biodiversity is ethical rather than practical. It clarifies research issues. Here I somewhat agree, in that I feel it is an ethical issue, as is murder and genocide.

The global loss of insect biodivsersity and numbers is well known (Nothing but Native with Doug Tallamy, 2022). Notably Vellend (2017) refers only to plants for his evidence. What about the rest of the ecosystem ? There is a good reason for this omission which amounts to selecting information that supports the message.

The lappet moth caterpillar used to devour my hibiscus and hang in great hirsute colonies on the thorn tree. This is the only one I've seen in years. The plants are still there.

The lappet moth caterpillar used to devour my hibiscus and hang in great hirsute colonies on the thorn tree. This is the only one I've seen in years. The plants are still there.Isn't loss of biodiversity insignificant ?

Vellend (2017) also claims that no one has proved that slight biodiversity loss leads to loss of ecosystem services. So those who do claim this are not basing their argument on science. Here I feel is where the double edged sword of utilitarian reasoning (Chigonda, 2017) cuts and life bleeds. A scientist looking at the utility of an ecosystem inadvertantly encourages policy makers to think that a little degradation and loss is acceptable.

But biodiversity loss, climate change and all of the systemic and environmental changes are cumulative. One human being may not see much of a difference in their lifetime (Though I have, and my 93 year old mother surely has) but add up all the small losses which seem to do no harm to ecosystem services on the time scale of a human life, and you will have massive harm over a few generations.

We may not even realize what a degraded landscape we inhabit at present, and just have no way of feeling what life was like before, as the memory dies with the people that pass on, and the only record is in some perhaps dull figures and statistics that batty people shout about, and grainy old movies and photographs without enough detail. This degradation could go on, getting slowly worse, until life becomes untenable.

Won't evolution fix it,

like it did before we came along ?

Vellend talks about speciation rates and this is where the argument gets interesting. He claims that the speciation rate is 6 times the extinction rate, that is 6 times more species are created than destroyed. He emphasizes that there is a large difference between actually recorded extinctions and projected extinctions. But he is talking only about plants !

Vellend refers to hybridizations as the means of creating species but not to their negative, species removing effects, which I'll elaborate on later under 'Fynbos'.

He adds that plants seem to be immune to the mass extinction events of the past ! Doesn't this say we can't look at plants to determine whether we should be worried about extinction events, or use them as scientific evidence to argue there is no 6th mass extinction occurring ?

But this is exactly what happens.

Evolution

EvolutionWhy worry ? ...

'Nature' will balance itself. It always does.

An argument I've heard, which combines the toxic iconoclasm of Pyron and Vellend, but coated with a bit of 'Nature' woo by some folk in certain gardening movements, is that moving species around the world doesn't lead to permanent loss. The organisms will evolve and the system will balance itself again, as it did before man came along.

That is wonderful feel good news. It may indeed be true by the time New York and Mumbai are unearthed from under layers of rock in the paleontological record by some future civilization. Or, perhaps if man became extinct and his interference disappeared from the earth, it would recover the same levels of diversity it used to have in a few million years.

The speed at which the losses are occurring, the freedom of movement of species and the scale of man's interference is advancing, not slowing down but increasing.

Against this the slow pace of a lot of evolution nullifies this cheery bit of self justification for our lifestyles. Evolution's pace varies in different contexts. Viral and bacterial adaption is rapid, plants hybridize in a matter of seasons, but man took 6 million years to evolve from an ape ancestor and we've disrupted most ecosystems on the planet in just 300 years.

This type of “nature will take care of it” thinking is as bad as the profit motivated oil industry's self serving discourse on the resilience of nature. Someone or something else, later, not now, will have to clean up after us, is common to both.

Actually no one is denying that there is

loss of biodiversity !

Pyron's inflammatory words did spark debate, a broadening of the concept of biodiversity, even a wish to abolish it. But the fighting in the public sphere is not actually about whether or not there is loss of biodiversity. The argument is about how we should react, what to call it, about the politics of its progenitors and how the science should be interpreted. All around the world, in many different contexts, most people care, whether their reasons are provided by ancient myths, spiritually based ethics, indigenous knowledge, current emancipatory movements, ecology, science or global law.

Should we care about them ?

Should we care about them ?What are our reasons for caring ?

Reasons for preventing loss of biodiversity take two directions (American Museum of Natural History), extrinsic and intrinsic. The extrinsic reasons are the most popular, and found in most writing on biodiversity. The thought is that biodiversity is important because of the services it offers to mankind, which fall into the arena of human health such as food security and medicines, or environmental health, such as water and air quality, the health of soil and ecosystems, and the stability of weather patterns.

Extrinsic reasons for protecting biodiversity

Below are the most frequently seen extrinsic reasons given for the importance of biodiversity. They are important, for one as fuel in debates with people who don't see the point of anything that doesn't benefit man or boost the economy.

Biodiverse ecosystems provide a swathe of ecosystem services:

Quality of life: people feel better in nature (U. Wageninen)

New medicines derived from plants, fungi and micro organisms.

Buffering against the transfer of zoonotic plagues such as covid from animals to humans

Lessening the spread of malaria by reducing the mosquito's habitat

Food security: 2/3 of our food comes from 9 crops whereas there are 6000 we could grow and make use of (University of Wageninen, 2022).

Nutrient dense foods which combat malnutrition

Indigenous produce adapted to local conditions and far more resistant to insects (Quinney, 2022).

Wild products on which the majority of the global poor depend, including the 1.6 billion people depending on forest products

More than half the world's GDP which is wholy or moderately dependent on nature

Water provision as ¾ of jobs depend on water

Healthy water cycles and ground water replenishment

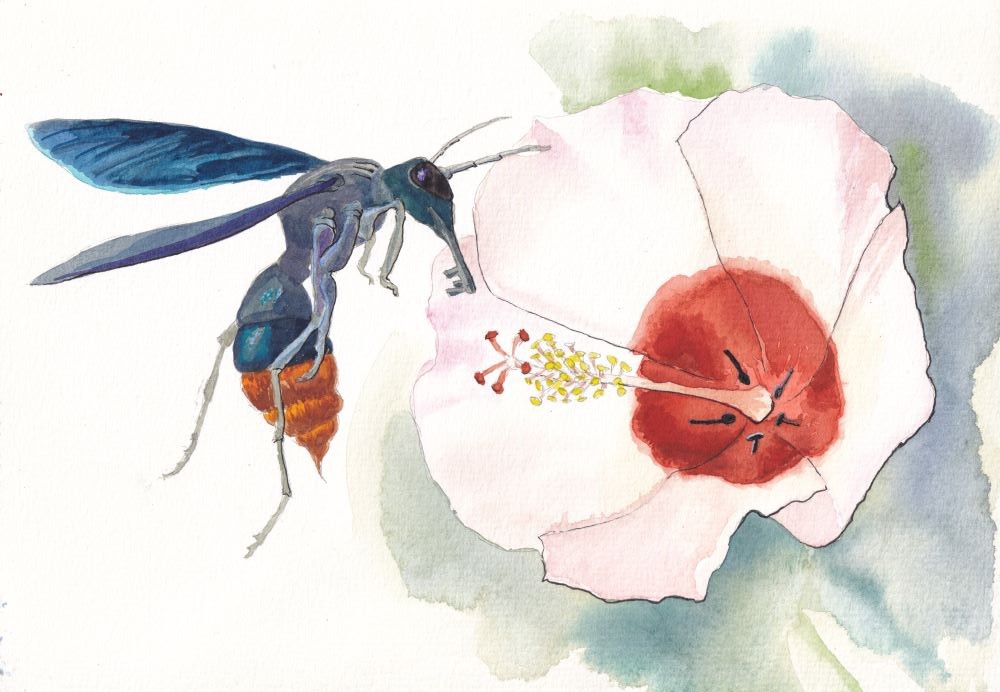

Pollination has enormous economic value. The almond orchards in California require the biggest bee relocation event in the world. But some bees there have it easy... just doing gardens.

Pollination has enormous economic value. The almond orchards in California require the biggest bee relocation event in the world. But some bees there have it easy... just doing gardens.Economic value as we get 125 trillion dollars of value out of natural ecosystems every year (Quinney, 2022).

Employment because the resorative economy, restoring natural landscapes, provides more jobs than the extractive sector (Quinney, 2022).

Eco tourism opportunities such as coral reefs

Agricultural pest resistance through supporting beneficial organisms

Prevention of floods and soil erosion

Air filtration for dust and other pollutants

Diverse ecosystems sequestering more carbon

Diverse ecosystems offering greater protection against fire and weather events

Diverse native ecosystems helping protect coastlines and mangroves protecting against floods due to sea level rise (Quinney, 2022).

Native coastal plantings even reduce the impact of Tsunamis (Miyawaki 2014).

A carnivorous beetle on a Zantedeschia aethiopica flower

A carnivorous beetle on a Zantedeschia aethiopica flowerIntrinsic reasons for preventing loss of biodiversity

The intrinsic value of biodiversity is its value in itself. Justifications in this vein are the importance of biodiversity to the spiritual and cultural part of man, as seen in Conservation International's website (Shaw, 2018). However, I feel this comes back to homo-centric reasoning again. Then there is the issue of rights (American Museum of Natural History), or the right of organisms to exist (Heslop, 2021). I do not know quite how we justify biodiversity in a purely intrinsic manner. It involves justifying something outside ourselves without leaning on our needs, feelings or understanding, and its probably not possible. We can't give justifications truly intrinsic to biodiversity itself for wanting to preserve it.

Chigonda (2017) makes a good argument against utilitarian justifications for preserving biodiversity. She is in favour of intrinsic motivation :

Utilitarian reasoning is a two edged sword, Chigonda writes, that encourages disrespect for that which is not of utility to man.

She points out that utilitarian reasoning is too human centred and doesn't give a reason to protect all species, only a subset that are or may become useful.

She sees conservation of biodiversity as an absolute moral imperative, and a spiritual obligation to care for God's creation that is featured in most religions.

She feels that the moral imperative is the only justification that does not stand on shaky legs.

Is it so hard to just respect other life ?

Human arguments aside, the fact is that biodiversity does exist outside ourselves and it doesn't bend to our will. We can destroy it but manipulating it, recreating it or replacing it is something we're ridiculously bad at, so some reverence for a thing that works without us would be great. Keeping and supporting what is there should be central to our attempts to have a biodiverse world.

Tallamy lists bright white lights as a major threat to insects. They can also literally drive your neighbours crazy due to sleep deprivation.

Tallamy lists bright white lights as a major threat to insects. They can also literally drive your neighbours crazy due to sleep deprivation.Threats to biodiversity

Human activity has destroyed 83% of all wild mammals and half of all plants (Quinney 2020). 1 million species of organisms are threatened with extinction (University of Wageninen 2022).

As with climate change one of the biggest threats to biodiversity is the people saying there is no loss of biodiversity. They create confusion and slow down our corrective behaviour by decades if not centuries.

The threats to plants, insects and soil life

In the rest of this article I will only discuss insect diversity, soil microbe diversity, and the connection to native plants as they are within the reach of the gardener. Wolves have righted things in some regions of the world. I do have Australian friends with a garden friendly to large Marsupials, and a sister struggling with managing deer, so large animals can also be part of the system of course. However, most of us work on a smaller scale. If you live near a nature reserve or have a large property, definitely consider the larger organisms in your planning.

Not only are soil, native plants and insects levers within the reach of the average gardener with a smaller property, I hope in this course to illustrate that they are foundational to the rest of biodiversity.

Exotic plant invasions

Both plants and insects are a foundation for the above ground food web. The link between the health of native plant ecosystems and insect diversity is well known. Patches of exotic plants that are invading natural habitats support a fraction of the varieties of insects supported by native vegetation. The order of magnitude (Tallamy, 2022. 16:14minutes) is in the region of 4:1 for diversity and 14:1 for numbers. That is the native vegetation may support 4 times the insect species and 14 times the total of insects. Many other animals depend on insects and with the loss of insect diversity and numbers, these other animals are also in decline. For example insectivorous birds are in decline in north America and Europe, whereas other birds are less affected (Tallamy, 2022).

However in a food garden, choosing food plants which are also good for insects such as pollinators, even if the plants are exotic is of course beneficial in sum. It is better than choosing food plants which do not benefit insects. In many regions of the world exotic food and other flowering plants can offer bee forage for a longer season, as the wild plants will tend to have a much shorter flowering period (Chadwick et al, 2016).

Metaphor for specialization

Metaphor for specializationHost-insect specialization

Specialization is both one of the wonders of nature and one of the greatest dangers to biodiversity..... if it is ignored !

Insects pollinate 80% of plants in north America, at least, so if the insects are lost, most of that 80% of plants will not be able to reproduce. Pollinator plant relationships are often specialized (Brooklyn Botanical Garden, 1994) with the insect mouthparts evolving to fit the nectaries of the flowers. Caterpillars and larval insects are also often specialized on particular host plants because they have evolved to tolerate the plant's defensive poisons. Insects such as butterflies will have this lock and key relationship with their nectar source as butterflies, and their food sources as larvae. If either of these plants disappear, the insect will disappear too.

Thus it should be clear that one way well intentioned gardeners can suppress insects is by planting pollinator plants without planting for the larval forms (Tallamy, 2022). Make sure the pollinator garden does not ignore that the butterfly was once a caterpillar and that it takes many caterpillars to produce one butterfly.

Pollution

Insects are declining for many reasons. Tallamy says habitat loss is the greatest driver of decline. This includes exotic plants invading and replacing the native vegetation that the insects need. Another cause is spraying poisons. These also poison the insect eating animals higher up the food chain. They also decimate soil life. White lights, which abound in cities, destroy many insects whereas yellow lights, or lights which turn on only when they are triggered by a sensor, do less damage (Tallamy, 2022). in sum:

Habitat loss through farming, urban development and plant invasion

Poisons: biocides, disinfectants, fertilizers

White security lights

Knowledge

Knowledge is another aspect of our relationship with biodiversity that plays a double role and can be seen as a threat. What we 'know' may get in the way. The little we know about ecosystem function, the deficit of knowledge that exists for all mankind at this moment in time means we're working with a black box. The spread of knowledge on biodiversity is also very unequal.

The Cape Fynbos:

an example that has some universal traits

PLANTS

I'm positive many areas of the world share these concerns. Cape Town is losing its plants. It is the city with the greatest number of red data plant species in the world (Botha and Botha, 2000). This is because the city was established and expanded right on a plant biodiversity hotspot. Many cities are situated on diversity hotspots, because when people first settled there it was advantageous.

At the Cape, contrary to Vellend's claims, hybridization of plants has led to some biodiversity losses if you look at the whole picture. An example is the hybrid of Celtis africana (native) and Celtis sinensis (exotic). Celtis sinensis-africana hybrids are taking over so that in effect Celtis africana is becoming extinct. The net gain is zero species and the loss of the far more attractive Celtis africana. Another example is the hybridization of natives from a specific locality with the more showy horticulturized flowering plants available in nurseries which may originate thousands of miles away. They create Frankenstein plants. The flowers of these Frankensteins are useless to local specialized insects as they have different nectary structures.

On the ground, in the Fynbos, which has enough plant diversity not to need a foreign injection, I've never met anyone enthusing about exotic plant genetics blending with our own. More often it is a calamity leading to loss, not gain.

Bietou (its Khoekhoegowab name): Is it a keystone species ? It is a great insect host plant, has berries enjoyed by man and other animals. In a reserve nearby it is dominant, perhaps a pioneer. How to get more information on its inter species relationships ?

Bietou (its Khoekhoegowab name): Is it a keystone species ? It is a great insect host plant, has berries enjoyed by man and other animals. In a reserve nearby it is dominant, perhaps a pioneer. How to get more information on its inter species relationships ?INSECTS AND PLANTS

keystone species

Locally, we really need more information to help us support insect diversity. We don't have enough knowledge to slow biodiversity decline significantly. Even local biodiversity activism groups focus on plants, and as discussed, this is a group least hard hit by extinction events. With 8000 plants native to our small sub-region, we don't know, bar a few prominent popular examples, which plants support which insects. The well known examples of keystone species interact with insects in guilds so small they cannot save the Fynbos. We also don't know what habitat to provide in terms of soil, moisture and shelter. Most people stop at some pollinator plants for honeybees, a bird bath and an insect hotel. That is a great help but we could have greater biodiversity with more diverse habitats. There should be more information on what will be the most effective habitats to create in our region.

Calorie conversion in ecosystems

In much of the northern hemisphere caterpillars are the biggest converters of plant calories to animal calories, supplying energy to the whole food chain (Tallamy, 2022).

Doug Tallamy teaches ordinary people about the importance of caterpillars in the food chain in north America but I've struggled to get information on the most important insects for converting our plants to animal flesh, and the plants they thrive on. It would be empowering to know them so that we can support the insects and the birds and everyone else.

In the Cape we are butterfly poor (Proches and Cowling, 2006). Other insects and animals must pollinate and convert calories. We have flies, ants, wasps and mammals doing the pollination.

I assume insects like termites do a lot of the calorie conversion. In Plattekloof arboretum underground termite colonies push up lush green 'fairy circles' in the grass which flush with mushrooms in the rainy season. I never get tired of them, even if the mushrooms are inedible. The green circles inspired the name 'Tygerberg' translated as 'leopard mountain' for the rump like hill that is dotted with darker green.

My mother observes that in the small areas of indigenous forest, insect feces rain down continually from the canopy. They are of all different sizes and patterns, indicating different insects as the source. But which insects are these, and which trees are they feeding on ?

I'm convinced we can do better !

Why do we need to know which are our keystone species for calorie conversion ?

Because with a choice of 8000 plants growing in the Cape Floral Kingdom and the average garden only being 100 m2 or much less, we do need to make the most effective choices and eliminate some. I think that knowing how to get the best leverage with our planting is very helpful. People in north America know what the levers are. Why do we, in this place of specially high plant diversity, not know ?

Compared to gardeners in South Africa the wildlife gardeners of England and the prairies are very well informed. Regional information centres teach what gardeners need to know to get started. Many more people, including nurserymen, are pushing the agenda.

There is good stuff to be had in black and white. People from all over have been studying the fynbos for centuries and writing about it, and I hope many more will. I'll be citing these excellent references in the course.

There is good stuff to be had in black and white. People from all over have been studying the fynbos for centuries and writing about it, and I hope many more will. I'll be citing these excellent references in the course.Biodiversity and biodiversity knowledge

in inverse relationship ?

The north is less biodiverse than the south. This is globally true as biodiversity increases towards the equator (Vellend, 2017). However northern biodiversity is better protected. The north has a much greater density of observers, researchers, citizen scientists and money. In many countries in the south we don't have the funding or the popular motivation to make biodiversity important, and poverty is the main reason given. It sabotages these types of concerns.

Inspiration from the global south !

Nonetheless, despite some handicaps, people in many southern countries do wonderful things by just acting out of passion and conviction. India's forest builder Shubhendu Sharma, the country's numerous water activists like Rajendra Singh, and seed activists like Vandana Shiva, Kenya's tree planters in the tradition of Wangari Maathai are just a few examples that pop up but there are many many more heroes and heroines of biodiversity in the south who have risked life and limb to fight for nature.

It would be hard to catch up with the north in terms of citizen science engagement, never mind attain the same number of experts per species. However, we should not be discouraged by comparisons, but motivated.

I admire people who make things happen, and have an enormous drive to spread the love for the potential beauty on our doorstep, such as the organizers of UWC's numerous citizen science projects (van Breda, 2023).

I visited a UWC small mammal survey with a friend, where members of the public can accompany scientists on their data gathering in the Cape Flats Nature reserve which is situated like an island in the middle of the city.

The event was one continuous learning experience. I didn't know we had Gerbils here, let alone that they were so common. I didn't know that caracal roam the city's townships using culverts and water courses.

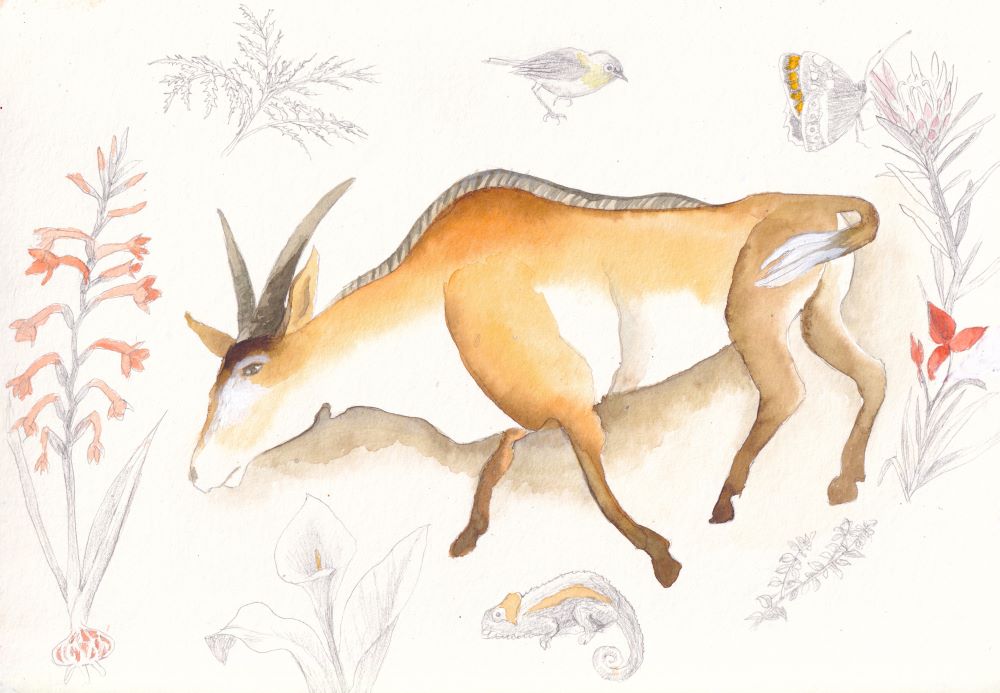

The sacred eland was a frequent subject in cave paintings, this copied from a beautiful example near McLear. Imagining him surrounded by mythical fynbos in natural earth colours .

The sacred eland was a frequent subject in cave paintings, this copied from a beautiful example near McLear. Imagining him surrounded by mythical fynbos in natural earth colours .Give indigenous knowledge more room !

One good thing we have in the Cape is that a lot of local people know about the practical use of our plants. Modern humans have occupied this region for longer than any other place on earth. There must have been much good nutrition here to sustain the ancestors of mankind for so long. The flow of knowledge down the generations has survived calamity and oppression. It has been upheld by special people who engage with plants out of love, need or calling. If we could treasure the folk who are a storehouse of this knowledge, and save it for the future, that would be a wonderful thing. If we could all fill our gardens with indigenous medicinal and food plants, plant and insect biodiversity in the city of Cape Town could flourish as many of the edible plants support insects because they are palatable or have nectar.

Local horticulture could do better

Indigenous knowledge is not valued enough in local horticulure, and most nurseries and farms cater to non-indigenous gardening and food ideas. Nurseries here are often geared to decorative gardening in the English or Italian style and to European vegetables. The rose is the pinacle of garden plants and the chemical companies must love that.

Apparently that is what people want, but a nurseryman holds a privileged position as the shaper of our urban vegetation, and should be an educator too. It is hard surviving in that industry but one need not guide the customer into selecting exotic hedging and other plants in functions which could be better served by native varieties.

The customer educated by the plantsman and nursery staff will not complain, and the business won't lose sales. I've worked in the industry and was frustrated by the average nursery's lack of effort to educate their buyers.

Plants stabilizing the dunes. But is this a God made vegetable patch ? The green fuzz in the background is edible.

Plants stabilizing the dunes. But is this a God made vegetable patch ? The green fuzz in the background is edible.The massive eco-nomic potential

of local edibles

The nurseries do not stock the native edibles and medicinals beyond a common handful of aromatics seen everywhere that you can use for decorating cakes and making perfume or tea.

Wild vegetables would open new markets, add to revenue and diversify the palette of garden plants. There is nothing as wonderful to see as wild asparagus crawling with bees when it flowers. Tetragonia decumbens caps and stabilizes our windswept dunes, looking like green sauce poured over a pile of icecream. In the vegetable garden it tumbles over the edge of straw mulched raised beds, growing happily next to amaranth, maize and beans.

There are many other exciting gems. Stocking indigenous food plants would support invertebrate diversity in the whole ecosystem of Cape Town, improve food security and stimulate our food culture. Most of all, our native vegetables don't need inputs. This is a wonderful advantage in times of dwindling resources like water and fertilizers.

Putting a bee friendly sticker on an exotic pansy to try to cater to the public's thirst for biodiversity is a kind of deception ! One can so easily do better.

A hot dry mixed vegetable border along the drive. The fine leaved vegetable is the same wild plant from the seaside above. It grows happily with African amaranth, maize and blue peter beans.

A hot dry mixed vegetable border along the drive. The fine leaved vegetable is the same wild plant from the seaside above. It grows happily with African amaranth, maize and blue peter beans.Endangered soil microbes ?

Very few people know how to rehabilitate our terribly damaged soils. From what I've read on soil life in the fynbos, our own soil microbiome must be very unique. The organization Communitree used to advocate a 3 year succession process to support our native climax plants in the third year or later.

The climax plants such as proteas and heather are difficult and succumb under conditions that make other plants thrive. Some of them are killed by small amounts of organic fertilizer, or watering in our long dry summers, or even the presence of exotic nitrifying bacteria ! One gardener I met says she uses vermicast effectively, but this may have been sales talk. If it works it is probably because it has such diverse micro organisms in it, so that there is something for the finnicky local plants to use.

A universal solution like increasing soil fertility as recommended by regenerative agriculture and modeled on the north American prairie is not going to help us grow the climax plants of the fynbos. I am not anti-regeneration, but pro creating a diversity of soil habitats, for the sake of biodiversity.

Around the world low nutrient soils have been found to be best for native flowering plant diversity. This is seen in writing on English meadow gardening, north American prairie gardening, German Naturgarten and especially the Hortus Netzwerk. This is mainly because fertile soil supports vigorous weedy growth which suppresses the flowering plants. In the Fynbos the flowering plants don't even like fertility, and some die when they get too much of it. This on top of the competitive weeds which rich soil brings with it.

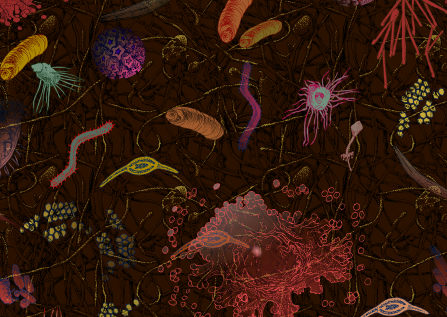

A jazzed up illustration of the major groups of soil microbes.

A jazzed up illustration of the major groups of soil microbes.Destructive types of imitation

No matter where we are, we should be careful of adopting solutions designed for other regions of the world. We should consider the practices and principles of gardening styles that we hear about and find out what aspects are truly universal. When the only information available is created by companies wanting us to buy their products, or the plethora of knowledge makers in other regions of the world it is easy to assume it is general knowledge and follow it and unknowningly ignore what is best for us. We need to create our own gardening culture and knowledge base because our climate and soils are different and unique, as are those everywhere.

IN SUM

So.. do we have a problem... really ?

Is there any consensus on loss of biodiversity ?

Despite apparent attempts to be controversial, and give the opposite message of the current discourse, I have not read any scientific paper which claims there is no biodiversity loss as a whole, globally, nor that any given locality is spared some loss in certain categories of diversity.

So there is scientific consensus that there is loss. If any areas of the world experience gains in diversity with plants, even the writers such as Vellend (2017) and Pyron (Fieseler, 2021) are careful to exclude clearing for agriculture and urban development which devestate natural ecosystems and reduce biodiversity always. There is no argument about development having a negative impact.

As suggested, there are so many kinds of biodiversity, at different scales, so that it is necessary to be quite specific about the type of biodiversity and the scale used, in order to avoid errors in generalizing. Worldwide, there is insect diversity loss and insects are foundational to the foodweb. Studies have found that invasive plants cause a loss in insect diversity according to Tallamy.

Bar the few scientific studies which are either consciously provocative or have a narrow focus on the group least affected by mass extinctions, plants, they all think we're in serious trouble.

Enhanced vision for nature lovers

Enhanced vision for nature loversAnd then we have our eyes and memory !

As a sixty four year old human being I have seen the wilderness around Cape Town ploughed up, built on and paved over in my lifetime, with very few isolated attempts to lessen the damage.

I know we have lost more than enough from talking to my father, now deceased, who surveyed the flood plains of our rivers, with swarms of flamingos and ducks which rose out of the reeds, and my 93 year old mother who ringed birds in our tidal marshes before the city throttled our water ways with concrete.

I have so much direct knowledge during my lifetime of loss just from having a garden. We have all seen this, if we've been around a while. Please share your experiences in the comments.

I have seen loss of species such as birds, insects and reptiles. The dawn chorus in my neighbourhood is gone, in just two decades. The knobbly locusts in the hedge which scared me as a kid, the ubiquitous chameleons, now no longer.

I frequently drive past the suburb of Rietvlei on our way up the coast with the dogs. There used to be a vast tidal marsh carpeted with red, gold and yellow green marsh plants, fringed with reeds and honeycombed with the blow holes of clams. The lagoon was used by 200 species of birds traveling from as far as Russia to visit us.

Then the tidal water levels were stabilized for rich people to build close to the water and have boats.

When I pass the kikuyu choked flats and the dirty brown water lapping the lawns of the sordid whitewashed fake Tuscan houses, my eyes burn with tears at what is there now, and after decades it hurts every single time. 2.4% of this country is wetland. There was plenty of other space which was not on such a rare and threatened ecosystem.

But there will be many who don't remember how it used to be. This is how the devastation creeps up on humanity insiduously.

As a human being I mourn all the lost animals in the water and the air, the buzzing, crawling, swimming, communicating, filtering, recycling alchemy of organic communities and the rarities, oddities and reliable functional organisms that thrived there, but as an artist I mourn the loss of beauty. Invaded Lagoons, Fynbos, Strandveld and Renosterveld look different to unspoiled originals. The loss of integrity is visible to the naked eye, and gone are the fabulous palette of colours, the purples, browns, greys, limes, beiges and blacks, the variety of pattern and form, to be replaced by a verdant, but toxic looking exotic vegetation. The change I have seen and cannot unsee it.

All the expert ecologists in the world grandstanding to attract attention cannot impress me, even if examining them added, I hope, some nuance to my opinions.

Is earth in trouble ?

Is earth in trouble ?Calling 911

All in all, biodiversity is in crisis. We may have different reasons for valuing biodiversity, but whatever they are, biodiversity is an issue because it is disappearing. Like being a good citizen involves offering help or calling emergency services when a pedestrian collapses on the street, a good citizen should be concerned when the earth's vital signs are changing for the worse, and act.

As Vellend acknowledges, when man interferes with ecosystems the results are unpredictable. It depends on the type of interference and the resilience of the pre existing ecoysystem. This tells us we need to be very aware of the consequences of what we're doing. Every land user must inform themselves on their ecological impact to the best of their ability and start new experiments cautiously.

The global loss of biodiversity is indesputible, even if local effects vary more. Contributing knowingly to loss of biodiversity for the sake of profit or convenience is unethical. Unfortunately the actions of a few unethical people can do a lot of damage. For the rest of us, this behaviour needs to be stopped by the law. It is a crime against future generations to rob them of a decent home, with resilient ecosystems and ecosystem services like clean air that we have enjoyed ourselves ! The law needs to be developed as its not currently equipped in most places. So far governments and international organizations have been our only means to stop ecological crimes against our descendants, and they have failed.

The creatures affected by our concern for biodiversity or lack of it, couldn't care less about our heated debates or use of language and while humans posture time is ticking. In 1992 a multilateral treaty, the Convention on Biological Diversity, was codified by the UN, but few of the biodiversity goals have been accomplished by the member nations to this date (Fieseler, 2021).

To be able to have any effect on the broader scale, working alone is ineffective, so I chose to join organizations that represent my concerns and support them. The power of the many is impressive when focussed.

What can a gardener do ?

The rest of this course involves

sharing with you whatever information and resources I've found that

help us decide what to do to increase biodiversity in our gardens. I

try as best I can to find universal principles we can all use, while always returning to the contex of my personal gardening project so that you are

constantly reminded of your own difference and uniqueness. Wherever

we are, we need each other to do this, and we need to be different.

That is the nature of diversity.

Restore Nature Newsletter

I've been writing for four years now and I would love to hear from you

Please let me know if you have any questions, comments or stories to share on gardening, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, food forests, natural gardening, do nothing gardening, observations about pests and diseases, foraging, dealing with and using weeds constructively, composting and going offgrid.

Your second block of text...

SEARCH

Order the Kindle E-book for the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023

Recent Articles

-

Geography Research Task

Jan 31, 25 11:37 PM

To whom it may concern My name is Tanyaradzwa Madziwa and I am a matric student at Springfield Convent School. As part of our geography syllabus for this -

Eco Long Drop Pit Latrines Uganda

Nov 29, 24 02:45 AM

Good evening from the UK. My name is Murray Kirkham and I am the chairman of the International and foundation committee of my local Lindum Lincoln Rotary -

Landscape Architect

Oct 01, 24 10:42 AM

I so appreciate your informative description! Your experimentation and curiosity with the seeds, germination, and rearing of the maggot are exciting to

"How to start a profitable worm business on a shoestring budget

Order a printed copy from "Amazon" at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

or a digital version from the "Kindle" store at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023