Dear Reader, in this age of AI created content, please support with your goodwill someone who works harder to provide the human-made. Sign up in the righthand column or bottom of this page. You will receive my hand illustrated monthly newsletter RESTORE NATURE and access to the biodiversity garden design course as I write...and nothing else, I respect your time.

Native berries:

A foundation of your food-jungle !

A bucket of local Numnum berries I used for making delicious wild yeast vinegar.

A bucket of local Numnum berries I used for making delicious wild yeast vinegar.I hope the newsletter has whetted your appetite and made you curious about why I think native berries are such a powerful ingredient in the food jungle. I want to lay out my reasoning for you here and by the end, either make you into a convert, deepen your conviction or at least give you ammunition !

I’ve read about berries in the main countries from which you, the readers, come. I was overwhelmed by the diversity offered in Brazil, Canada and the USA, Singapore, India and China. The list of possibilities, which is a shortlist, is approaching 200 species. At that rate, it is not possible to cover them in one article, or even a series of articles, nor is personal experience of growing them possible in one underfunded lifetime. What I can do at this stage is to encourage everyone to find out about their own native berries, because there are overwhelmingly plenty of them ! Striving for diversity in our diets and in the garden is a very good basic principle in any area of the world.

Seen in Paarden Eiland industrial area, a stripy eyed lagoon fly, Eristalinos taeniops on a local berry bush, a very productive host plant: Chrysanthemoides monolifera. Its indigenous Khoe name is bietou.

Seen in Paarden Eiland industrial area, a stripy eyed lagoon fly, Eristalinos taeniops on a local berry bush, a very productive host plant: Chrysanthemoides monolifera. Its indigenous Khoe name is bietou.What is a food jungle ?

I’ve built my garden unwittingly based on principles I’m calling ‘food jungle’ principles, in retrospect. This to differentiate it from the widely known idea of the ‘food forest’ because I find the support of wildlife a necessity and not a ‘benefit’ for myself and this shapes my choices. Basically its a food forest but a good deal wilder, less controlled, even less tidy, with more native species, and this is created as a support for all the non-plant life to thrive, including myself. You’ll find I borrow practice from permaculture, agroforestry, syntropic farming, insect and wildlife gardening and other sources which will be mentioned in the article, but I do not adhere to any one of these religiously.

But if you are designing a biodiverse garden of whatever kind, that locks down carbon in your soil and plants, and grows a diversity of nutritious plants, berries should ideally be foundational.

Why are wild berries so powerful and important ?

A Lappet moth caterpillar which feeds on several plants including our Vichellia Karoo, and exotic hibiscus. Its hairy body discourages predation.

A Lappet moth caterpillar which feeds on several plants including our Vichellia Karoo, and exotic hibiscus. Its hairy body discourages predation.BIODIVERSITY

Interdependence of caterpillars and native plants

Wild or native berry species will often be host plants for caterpillars.

But, being eaten leaf and all is not advantageous to a plant. The plant may develop protection by evolving plant poisons that slow down, repel or kill all herbivorous insects or render them infertile. Nearly all plants thus contain substances that are poisonous to some herbivores, be they large or small, as they are advantageous to the plant. Some caterpillar may gain an advantage over other insects by evolving a means to overcome a toxin, by chance mutation. Because of the investment in the evolution of this antidote, it is more likely they have resistance to just for one toxin. The caterpillar will be able to eat the leaves of a particular species and its close relatives with similar chemistry, or a few other plants using the same poison. This is why many caterpillars can only digest certain plants or plant groups, and are most likely to be suited to digesting local plants, due to their long association through evolution.

The consequence is that without this plant, the caterpillar cannot eat, and the adult or butterfly will not develop and procreate, and the species will die out. Thus for the maximum number of caterpillars we need native vegetation. You will see some caterpillars able to digest more different plants, and some exotic plants which are keenly devoured by caterpillars. This does not mean that for greater diversity, native plants are not needed. That is a misunderstanding of diversity. Lots of one species, or exceptions to the rule do not invalidate the need for native plants. For example, the cabbage white in South Africa eats our cabbages. This is because an introduced plant species is being used by an introduced butterfly and its larvae.

A cabbage white larva which defoliated the nasturtiums. They survived.

A cabbage white larva which defoliated the nasturtiums. They survived.Food webs

Caterpillars are the largest converters of plant to animal calories according to Doug Tallamy who is from the northern temperate forests. They sustain the macrofauna of the food chain, feeding birds, insects, reptiles, frogs and small mammals.

The interdependence of butterfly larvae with certain plants is not the only specialized relationship with native plants. In the Fynbos vegetation in my area, there are butterflies, but they are less abundant than up north. We have a slightly different set of herbivorous insects and energy sources, which I cover in another article on local biodiversity HERE. Nonetheless there are many lock and key relationships between plants and arthropods, especially in pollination. A well known example is the interdependence of long tongued flies and certain forms of flowers. This is as serious as it is an interdependence. Without the plant the insect dies out, and without the insect, the plant dies out, as it cannot reproduce sexually.

Thus the leaves and the flowers of native plants can be enjoyed and are necessary to specialized wildlife. The flowers of your native berries will also support pollinators, and the fruit will feed a range of birds on the plant, and a range of other creatures when they fall to the ground.

Cherries are in the Prunus family, one of the top three Genera of trees for caterpillar and thus butterfly support in Europe and north America.

Cherries are in the Prunus family, one of the top three Genera of trees for caterpillar and thus butterfly support in Europe and north America.Butterflies and berries

Recently I was watching an Austrian wildlife garden you-tuber interviewing a butterfly specialist. The butterfly lady explained that willows support a massive number of butterfly species, for example 100 species of butterfly larvae (caterpillars) feed off just one willow species the Salweide or salt willow. She also mentioned that some oaks support even more species of insects with 150 insect species using the common European oak. Prunus, oak and willow also support the greatest number of species in north America, and the parallels are interesting. Prunus being a good host plant is very good news for food jungle creators, as the genus includes cherries, plums and more.

According to the butterfly specialist the best thing you can do for butterfly diversity is plant the right tree. This way you can do the most for wildlife on the smallest area, call it the most bang for your bug. I was surprised. I normally think of flowering plants supporting butterfly pollinators, but we tend to forget the larvae, the caterpillars, and often do not even like them. A lot of caterpillars are needed to produce one butterfly, as the squishy grubs are the most common food for nestlings and many other creatures.

The Austrian wildlife enthusiasts also lamented the thousands of kilometers of Thuja hedges in Europe. This common hedge plant originates in East Asia or north America, and the European caterpillars can’t do anything with it. If only a small percentage of the Thuja hedges were replaced with the right productive indigenous hedge plants, even small fruiting trees or berry bushes, European insect diversity would get quite a boost.

The Rubus or bramble family are also hosts of a diversity of caterpillars.

The Rubus or bramble family are also hosts of a diversity of caterpillars.For the food jungle creator, many fruit and berry plants are excellent host plants. In north America Prunus is the most productive genus for caterpillar production ! Likewise in Europe, it is very productive for hosting Lepidoptera. Plants in the bramble and blueberry family are also good, with the common bramble topping the list. Remember the more tatty your leaves look, the prettier your butterfly garden will be !

Good butterfly supporting fruit trees are cherry and mirabelle plum. Strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, elderberry, wild grapes, gooseberries and currants also are host plants. In between the fruit hedge around your garden, you can also attract butterflies, bees and other insects with wild carrot flowers, fennel, soapwort, poplar, birch, lilac, privet and water lilies. Be careful not to have strong security lights. Rather use movement sensors that leave the light off unless there is an intruder, or use yellow light. With just that small adjustment you can do a huge amount to save butterflies and moths and give them time to breed and lay eggs.

The Austrian Lepidopterist recommends the Floraweb hitlist for butterfly plants, as a good resource for choosing plants in areas of the German speaking world.

The lovely seed heads of Leonotis leonurus add interest to the garden and provide insect habitat. I've seen a small wasp or fly visiting several tubes in quick succession.

The lovely seed heads of Leonotis leonurus add interest to the garden and provide insect habitat. I've seen a small wasp or fly visiting several tubes in quick succession.Some surprising enemies of biodiversity

Biodiversity is something many natural food growing movements and philosophies promise to serve but actually marginalize. In the case of berries this is done inadvertently, by our very natural human inclinations.

Firstly evolution is at fault. In the stone age past, getting enough calories was much harder and humans acquired a craving for sweetness to drive us to cover our basic caloric needs. Now we have a taste for large sweet luscious fruit, and to avoid the sometimes tiny, hard, bitter, acid and not very sweet wilder, more ancestral varieties. In many a food forest video the speaker will rave about the sweetness of the berries they are tasting and pretty little else.

This desire shapes horticulture. You’ll be told by food forest enthusiasts never to grow from seed as the resulting trees don’t bear ‘true to type’. But you may get a more ancestral variety growing from seed and this is actually a good thing. The fruit may be smaller and harder and more bitter but contain more health giving phytonutrients. You will also get a lot more genetic diversity in your plants growing from seed. We have raised small hard, green lemons with an exquisite perfume you would never find on a commercial lemon. Growing fruit trees from seed you may have to sow a lot and over-plant, but then you can cut back the excess, leaving the roots in the soil, and lay the branches down for nutrient cycling and the soil building work of microbes. Over sowing of trees is advocated by some adherents of syntropic farming as a very good turbo charger for your food growing ecosystem.

The collector's passion in many a gardener is the next culprit. Biodiversity is often marginalized by the collector’s desire for the unusual, their attraction to the unfamiliar, and this leads almost logically to yen for the exotic, when a collector could just as easily cultivate enthusiasm for native plants. There is plenty of rarity and lack of familiarity to go round. It is not necessary to become purist. A fifty fifty mix of exotics and native food plants would adequately provide for all the creatures that feed off the natives in your forest. Edward O. Wilson in his book Half Earth, advocates that half the earth should be left wild. This doesn't perhaps translate magically into a garden context, but why not maintain the rule in the microcosm too ?

The opposite impulse of the thirst for the exotic is also a culprit. The appreciation of what is familiar to the exclusion of all else. This takes the form of desire for the fruit one knows, and rejecting the rest.

Aesthetics can be the enemy of wildlife. Sticking to familiarity is a kind of conformity, but there is another kind relevant to jungle builders. It is the pressure to have one’s garden look a certain way to please the neighbourhood style police. Biodiversity is hugely damaged by the desire for tidiness as we all know. Deadheading and removing hollow dried stems, pruning and pulling up and removing all the weeds robs some creatures of their nesting, food and habitat. Picking up all the leaves and fallen twigs and branches and leaving the earth bare is destructive because the sunshine will kill microbes. Naked earth is dying earth as the regenerative agriculture people will tell you. But when you clear up you are also removing habitat, and even following your cleaning with mulching can be destructive. There are creatures evolved to eat the debris from your trees and to nest and complete their life cycles on the ground in the fallen leaves. Leave them be where they fall. Nonetheless, always keep your soil covered, and for the sake of the biology, living plants are much better than brought in biomass such as straw or wood chips.

This tiny foot width path is used for harvesting the berries in the hedge. I don't ever step off it as I'd probably impale my feet on thorns. Fluffy black earth has formed beneath the trees.

This tiny foot width path is used for harvesting the berries in the hedge. I don't ever step off it as I'd probably impale my feet on thorns. Fluffy black earth has formed beneath the trees.Biodiversity is also damaged by human access, and sometimes animal access. Your feet will compact the soil and this limits oxygenation and the flourishing of good soil building microbes in it. Chickens may be brought in to solve a fruit fly problem, and they will remove your pupating pests, and everything else, and scratch the surface which should ideally be left undisturbed. We have to establish priorities and this is a personal choice. I have a fruit fly problem on my guava tree. I have decided just to leave it alone.

Compacting human feet should be kept out of a forest. This I learned from Shubhendu Sharma’s webinar on forest building, and from my mother Pixie Littlewort who worked in the local forests on Table Mountain. To contain human access you can create paths to your fruit trees and never stray off the paths. These can be as narrow as possible, with the smallest possible footprint. Perhaps stepping stones or planks raised off the ground on bricks could help. Ensure the trees have a very large area beneath them in which no one ever treads.

SHELTER

Native berry plants can create a sheltering enclave of vegetation

If you plant the perimeter of your garden with a mixed hedge of small trees and shrubs it protects the interior of the garden. In a food garden this hedge can consist of berry bearing plants as well as trees and shrubs for nuts, coppicing, fuel, biomass, dense cover, attractive foliage or blossoms that attract pollinators, and in terms of non-human benefit, some host plants for small invertebrate herbivores.

I’ve found that the outer hedge is fantastic at changing the garden’s micro-climate. The hedge creates shelter for wildlife and food plants to thrive in the middle of the garden. I first found this out when practicing water wise gardening with which I started out a decade ago. A sheltering hedge protects the garden from drying wind, gives cool shade for some of the day, and also generates thick fluffy compost underneath its canopy.

The hedge also creates a zone of forest like vegetation along the edge, and the special type of ecosystem that involves, in miniature. It is a place to grow fungi, and support animals which live in fallen wood and piles of leaves. It is a place to grow shade loving, under-story plants and on the inner edge of the hedge, forest margin loving species. If you create more micro-climates and differing ecosystems or habitat in your garden you will increase biodiversity as you offer a home to a greater diversity of creatures and plants.

It is also in the nature of a hedge, as the perimeter in an urban garden, that it is a very long space compared to the bulk of the garden, and takes up a surprisingly large area in total, without intruding much on the garden interior. Thus you can use the hedge to increase your garden’s proportion of indigenous plants, and still have the centre of the garden to introduce some exotic plants. An exotic hedge that bears no fruit, or has no other purpose than a screen is a waste of an enormous amount of potential, especially if you have to fuss over it.

A backbone of native trees makes the best foundation, or backbone, for a food forest. Often they also make great pioneer species, as they change the local environment. I have found this to work really well in my food jungle at home. The native trees tend to be hardier and once established provide shelter which most importantly stabilizes humidity, and thus allows beautiful black fungal dominant compost to be manufactured under the trees without my input. This is a better environment in which more tender fruit trees can thrive.

The native berry plants also can fits into a succession development in this way. I was delighted to find that one of the oldest food forests in the world is as wild and unruly as can be and should be termed a food jungle. In New Zealand a landowner used native trees as a basis for a food forest containing 80 heirloom varieties of apple. It was built on wrecked, degraded land. I totally agree with their philosophy of restoring damaged places, rather than going into some pristine area and planting food plants there, and having a really negative effect on biodiversity in so doing. These admirable forest (or jungle) builders Robert and Robyn Guyton were filmed by a New Zealand permaculture film company doing excellent quality work. See the link at the end of the article.

A hedge of Carissa bispinosa or numnum berries, and Kei apples or Dovyalis caffra protect us and the sheltered front garden from the street and its heat, noise, pollution and drying winds.

A hedge of Carissa bispinosa or numnum berries, and Kei apples or Dovyalis caffra protect us and the sheltered front garden from the street and its heat, noise, pollution and drying winds.NUTRITION

Wild berries usually pack a punch nutritionally. Below some reasoning as to why.

Ignoring the botanical definition of a berry and referring to everyday language, a berry is a very small fruit in common parlance. In the past, and this goes back to the before the Neolithic revolution, humans did not select for the phytonutrient or nutritional content of fruit, how could they without chemistry and microscopes, but for size, sweetness, softness and colour.

So the smallness of the typical berry fruit may mean in some but not all cases, that they are less highly bred. But wild berries have certainly not been bred. If they have 'returned to the wild' becoming naturalized, then successive generations of propagation from seed totally unselected by humans may have returned them to a wild-like nutrient profile. Without human selection they have maintained much of the nutritional content. Commercial berries are highly bred however. If they are still very tangy with a distinct flavour, rather than just sweetness, they may have a lot of good nutrition still, as our taste buds are a good natural radar for these other chemicals that are so healthy. Tart, slightly bitter and unique fruity flavours are what you should be looking for rather than our natural appreciation of sweetness. A little hardness will provide fibre for feeding your beneficial microbes in the colon.

Carissa bispinosa or Numnum, a very yielding berry tree once it gets going.

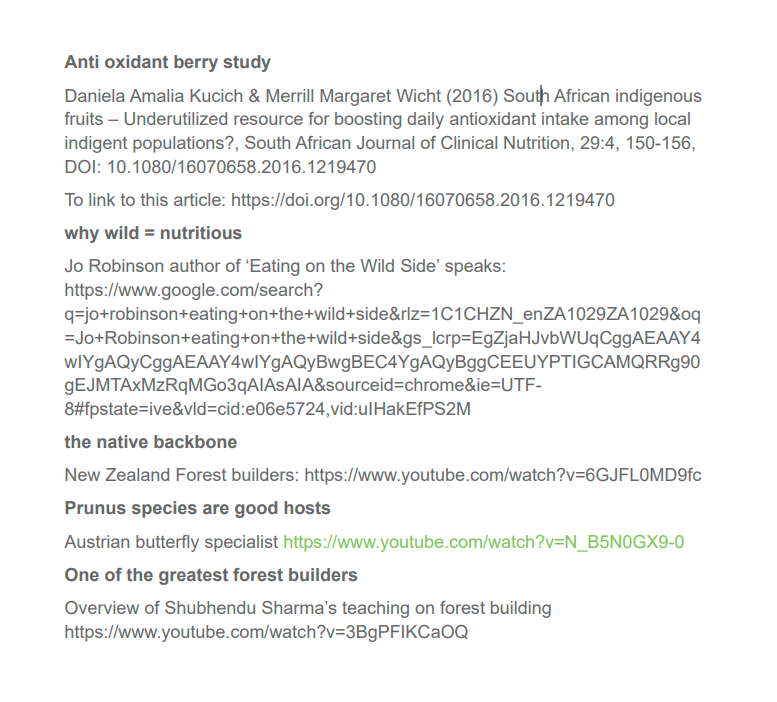

Carissa bispinosa or Numnum, a very yielding berry tree once it gets going.A study on the nutrient content of wild berries

Two chemists Daniela Amalia Kucich and Merrill Margaret Wicht at the institute of technology in Cape Town undertook a study (see the end of the article for sources) to argue that the right community education on local berries could hugely improve the nutritional status of rural children in poor families. According to their study it has been found that many rural children in South Africa eat a very monotonous carbohydrate based diet consisting mainly of exotic grains. The small percentage who eat fruit are mainly consuming bananas, oranges and apples and these are often unaffordable to most families and only 0.5% are making use of the abundant resource of wild berries which are free and far more nutritionally dense than these exotic fruit.

Quite small amounts of high anti-oxidant fruits will cover the dietary requirement for anti oxidants and phytonutrients to improve health and longevity. The authors of the paper set out to show that local berries are more than adequate, by comparing their anti-oxidant properties to two northern hemisphere berries, cranberry and blueberry, which are famous for their high levels of antioxidants. They combined three parameters of anti-oxidant action in a total count, and compared the cranberry and blueberry to ten local berries. These were chosen from the eighty lesser known local fruits used in rural areas, and the 32 used by contemporary Khoe-san foragers.

At this stage I found it necessary to take a pause to readjust my jaw upward. I was staggered. Eighty local fruits ! I never even knew this, despite focusing on native food plants for so long. Truly the region is gifted with plant diversity ! But be that as it may, this is a pattern. From my search on berries in the countries of readership I can confidently state that in nearly every region of the world the diversity of fruits in the wild will far exceed those cultivated or imported. The closer the country is to the tropics, the more diverse this wild resource gets. The difference between bought and wild here is staggering... 3 common exotic commercial fruits compared to 80 plus scarcely known and used local ones !

In the tests, the blueberry came in fourth and cranberry eighth, with our wild plum, then colpoon and wild olive in the lead. The wild plum, Harpephyllum caffrum has nearly twice the anti-oxidant power of the blueberry. Then came blueberries, christmas berries, crossberries, and cranberries, followed by waterberries, tortoiseberries, bietou, noem noem and sour fig (the invasive Carpobrotus in other regions of the world), in that order. In short, any of our local berries had a high enough anti-oxidant status to provide the poorest of the poor with sufficient anti oxidants that they could enjoy protection from disease and the life prolonging properties provided by the phytochemicals in berries.

More research to back up the use of native berries

If you’re not yet convinced, I was watching a David the Good video and he was commenting on the wild tomatoes in his garden and he dropped this reference: a book by the American journalist Jo Robinson called ‘Eating on the Wild Side’ and I found a video, now ten years old in which you can hear her speak on what she’s learned about wild foods and their nutritional quality from reading thousands of research papers.

Marvelous yellow raspberries Rubus ellipticus, an Asian native growing in north America in a relative's garden.

Marvelous yellow raspberries Rubus ellipticus, an Asian native growing in north America in a relative's garden.Food jungles in the concrete jungle

The berries could be planted as hedges or street trees in urban areas too, to benefit homeless people and the urban poor, and everyone else too. The aim would be both to get them closer and more convenient to consumers but also to preserve the species which would be most used, and protect their diversity in the wild. Also, foraging in the veld is not sustainable for a metropolis of several million people, and the resource would soon disappear.

I would love to develop food jungles on all the vacant lots in Cape Town, and I’m always growing extra plants to donate to community food gardens such as delicious wild asparagus and the anti oxidant powerhouse Harpephyllum caffrum mentioned above. Wild asparagus makes the European variety you buy in the shops taste really insipid by comparison. I have the buttery and yet intensely green perfume of its wild green shoots clinging to my hands days after harvesting ! I also encourage people to learn about and eat weeds. They are the high phytonutrient leafy equivalent of the high nutrient berries.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES APPLICABLE ANYWHERE

There will likely be far more native berries than commercial fruit varieties in your area

As suggested, the story of native berries is not unique to us. In every area of the globe the repertoire of wild berries is greater than the commercial fruit and many of these will outperform commercial fruit nutritionally because they are wild and unbred, and because the choice is so great the added benefit of dietary diversity will follow.

Red or sweet cherries were indigenous to parts of Eurasia and north Africa. There are at least 45 species of cherry if bird and bush cherries are included.

Red or sweet cherries were indigenous to parts of Eurasia and north Africa. There are at least 45 species of cherry if bird and bush cherries are included.Berry knowledge is precious

When

you know what native berries thrive in your local climate and soils you can

make choices that align with your plans for your garden and require

less maintenance. You can also include a huge number of them in a

garden perimeter hedge, just because of the length of it. However, finding out about your local berries

is the first challenge. It differs from country to country.

As an outsider searching the internet for information on the main countries of my readership the results varied a lot. If you Google wild berries from country X, you may find a resource like a local herbarium or botanical garden, or a Wikipedia article. In some countries there are nurseries which specialize in native plants and I assume all you need to do is go there and they will help you. In other countries its seems a Google search is not so useful. Sometimes there is not even something from Wikipedia, and the search results may be dominated by commercial berry farmers and traders and the berries that you will see are anything but wild, even when you use wild and native and indigenous as search terms. These local berries are a mixed bag of native and exotic fruit that are planted for commercial harvesting and export. These berries may be able to grow in the local climate and the search results are an indicator of what will grow, but they are not as useful for many reasons as the plants that grow naturally in the wild and are indigenous to the area.

If Google is unhelpful in your search, you will need to refer to local knowledge, such as an old person who forages in the area, or someone who knows your wild plants very well. Gathering information this way is slow, so start as soon as you can and keep it up for years. Another option is to go to a scientific source that is less clouded by commercial interests, such as a book on the plants of your region. Sometimes botanists do not know about the cultural uses of a plant. You will need to keep your ear to the ground, or your radar up, and over time, the information will come. When you have your information, please record it and write about it for future generations !

There are also ways of testing the toxicity of plants by experiment, but I don’t want to delve into that here and perhaps lead to an awful accident happening.

I found doing the country by country lists very exciting, and learned a lot. One of the things I realized is that I cannot cover them all, as first intended. An obvious reason is the sheer number of plants, and the major reason is that I cannot hope to speak with experience about them all, even if I had infinite resources. In every region of the world, only the locals can really become masters of native berry knowledge in all its diversity. An outsider is blocked by the obstacles of number, distance, climate and much more.

I can see from the search results the well known truth that diversity increases as you approach the tropics, but unfortunately, this also spreads the scientific scrutiny more thinly. Thus I learned that there are a large number of wild berries in every global region, and a deficit of knowledge in some places, both in terms of recorded use in the past, and current community knowledge. There is a huge need to research and record wid fruit scientifically, but also to teach of their use and cultivation, so that all citizens can prepare, enjoy, grow and harvest them, and keep them as part of local food culture for the sake of human health.

Ribes rubrum the red currant is native to western Europe.

Ribes rubrum the red currant is native to western Europe.Yet native berries have some surprising enemies !

There are so many reasons to love berries. However, as you grow your plants you will find that they have some enemies. Some are insects and other herbivores. You can rejoice in their feeding and the biodiversity they represent. A chewed leaf is a sign of a successful life-supporting food jungle.

Their other enemies may be human, and may not share your enthusiasms. Some hostility is founded on myth and some on inconvenient reality. Berry plants, apparently, make birds and bats poop on your car and garden walls, and bring unwanted animals like said birds and bats, as well as lizards, snakes, caterpillars, spiders and stink bugs to the neighbourhood. They can look messy, whereas gravel, concrete, tarmac or lawn are ‘neat’.

These problems are not impossible to solve if one makes the wildlife a priority. One can avoid parking a squeaky clean white vehicle under a large berry producing tree. One can paint the garden walls the colour of the most predominant and irritating poop as camouflage. Berry bushes do not attract snakes ! They have to be in the area, and if they can escape into the bushes rather than be cornered against a wall, are far less dangerous. Some people even argue that it is a privilege to have an apex predator visit your home. Others make the point that these creatures were here first, for millions of years before the automobile, and who are we to say that any space they share with us should be used for our needs alone ? Perhaps more people need to learn to appreciate the good that these creatures do, but to value them for their mere existence, intrinsically is generally enough for those of you who are already convinced, and just happy to be blessed by the presence of all this life. Messiness, like beauty, is very much in the eye of the beholder, but there is also an illogicality to these standards. We should not impose on natural systems the same kind of geometry we find in constructed places like building interiors where we've used straight edges. The imposition is bound to constrain the natural system and to make work for us as we try to make it to conform to a shape it never evolved to take.

A local wild Solanum variety. iNat has suggested the ID S. guineense. I cannot ascertain if it is edible as the same name is used for different plants by different authors.

A local wild Solanum variety. iNat has suggested the ID S. guineense. I cannot ascertain if it is edible as the same name is used for different plants by different authors.Berry expertise needed globally

It looks as if despite how things may vary around the world, there is a need to make propaganda for and teach the uses of these wonderful plants in every locality. They are designed by nature to offer us their wild, health giving fruit and ecological benefits in the hope of a mutual win win relationship, that you, or some other fructivore, will spread their seed ! How can we refuse ?

SOME USEFUL RESOURCES

Restore Nature Newsletter

I've been writing for four years now and I would love to hear from you

Please let me know if you have any questions, comments or stories to share on gardening, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, food forests, natural gardening, do nothing gardening, observations about pests and diseases, foraging, dealing with and using weeds constructively, composting and going offgrid.

Your second block of text...

SEARCH

Order the Kindle E-book for the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023

Recent Articles

-

Geography Research Task

Jan 31, 25 11:37 PM

To whom it may concern My name is Tanyaradzwa Madziwa and I am a matric student at Springfield Convent School. As part of our geography syllabus for this -

Eco Long Drop Pit Latrines Uganda

Nov 29, 24 02:45 AM

Good evening from the UK. My name is Murray Kirkham and I am the chairman of the International and foundation committee of my local Lindum Lincoln Rotary -

Landscape Architect

Oct 01, 24 10:42 AM

I so appreciate your informative description! Your experimentation and curiosity with the seeds, germination, and rearing of the maggot are exciting to

"How to start a profitable worm business on a shoestring budget

Order a printed copy from "Amazon" at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

or a digital version from the "Kindle" store at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023